By Dhanapal Govindarajulu, Divya Gupta, Ghazala Shahabuddin*

British colonialism turned India’s tigers into trophies. Between 1860 and 1950, more than 65,000 were shot for their skins. The fortunes of the Bengal tiger, one of Earth’s biggest species of big cat, did not markedly improve post-independence. The hunting of tigers – and the animals they eat, like deer and wild pigs – continued, while large tracts of their forest habitat became farmland.

India established Project Tiger in 1972 when there were fewer than 2,000 tigers remaining; it is now one of the world’s longest-running conservation programmes. The project aimed to protect and increase tiger numbers by creating reserves from existing protected areas like national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Part of that process has involved forcing people to relocate.

In protected areas globally, nature conservationists can find themselves at odds with the needs of local communities. Some scientists have argued that, in order for them to thrive, tigers need forests that are completely free of people who might otherwise graze livestock or collect firewood. In a few documented cases, the tiger population has indeed recovered once people were removed from tiger reserves.

But in pitting people against wildlife, relocations foster bigger problems that do not serve the long-term interests of conservation.

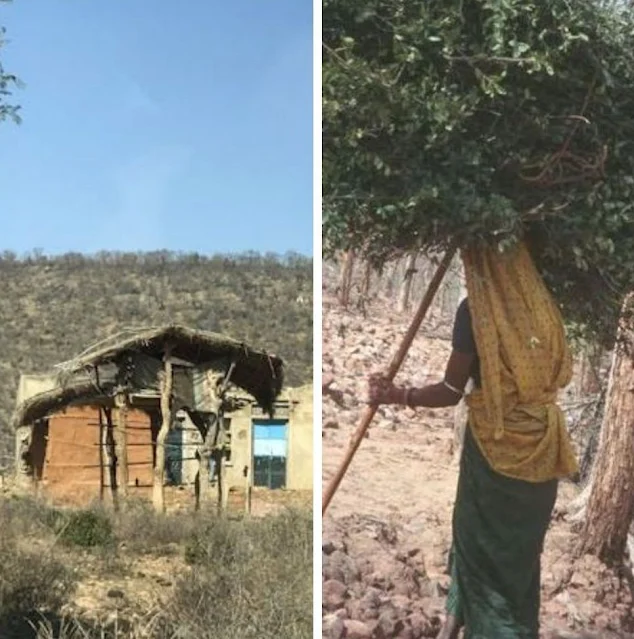

About 3,000 families were relocated from these core zones in the first three decades of the project, and from 2005 until 2023, about 22,000 families were moved. Most relocations were involuntary and some plunged those ousted into deeper poverty.

In Sariska tiger reserve in Rajasthan, northwestern India, the first relocation was made during 1976-77. Some of the families returned to the reserve after being given land unsuitable for farming as compensation. This was a poor advertisement for relocation which few other communities opted for voluntarily.

After they were moved from Rajaji tiger reserve in 2012, Gujjar pastoralists who make their living grazing buffalo were prompted to take up farming on new land. With little experience in agriculture, and having been denied their traditional source of income, many struggled to adjust.

The Gujjar did at least gain access to water pumps and electricity. In one case, in the Bhadra tiger reserve in Karnataka, southwestern India, relocation was less painful as people were offered quality agricultural land who already had prior farming experience.

Most people who lost their right to graze livestock or collect forest produce in newly established tiger reserves went on to labour in tea and coffee plantations or factories.

Despite widespread relocations, the tiger population in India continued to plummet, reaching an all-time low of fewer than 1,500 in 2006. Tigers became extinct in Sariska and Panna tiger reserves in 2004 and 2007 respectively.

Local extinction in Sariska prompted the government to enlist the help of tiger biologists and social scientists in 2005. This task force found that illegal hunting of tigers was still happening, their claws, teeth, bones and skin harvested for use in Chinese medicine. Mining and grazing had also continued within many reserves.

Similarly, in Parambikulam tiger reserve in Kerala, a state on India’s tropical Malabar coast, communities that were not relocated found work as tour guides and forest guards. People here have supplemented their income by collecting and selling honey, wild gooseberry and medicinal spices, under the joint supervision of the community and forest department officials. Many families have been able to give up cattle rearing as a result, reducing grazing pressure on the forest.

Despite these successes, the government’s policy of relocation remains.

Tiger numbers have recovered to more than 3,000 as of 2022, but Project Tiger shows that relocation alone cannot conserve tigers indefinitely.

A great opportunity awaits. Over 38 million hectares of forest, suitable tiger habitat, lies outside tiger reserves. Declaring these forests “corridors” that allow tigers to move between reserves could reduce the risk of inbreeding and local extinction and reinforce the recovery of India’s tigers.

Studies in certain tiger reserves show that large numbers of villagers would support further relocations if it meant gaining access to drinking water, schools, healthcare and jobs in resettlement sites. A portion of the US$30 million (£22.7 million) spent annually by Project Tiger should be used to make relocations fair. Or better yet, promote the kind of community-based conservation nurtured in the Biligiri Ranganathaswamy temple and Parambikulam tiger reserves.

---

*Dhanapal Govindarajulu is Postgraduate Researcher, Global Development Institute, University of Manchester; Divya Gupta is Assistant Professor, Binghamton University, State University of New York; Ghazala Shahabuddin is Visiting Professor of Environmental Studies, Ashoka University. Source: The Conversation

British colonialism turned India’s tigers into trophies. Between 1860 and 1950, more than 65,000 were shot for their skins. The fortunes of the Bengal tiger, one of Earth’s biggest species of big cat, did not markedly improve post-independence. The hunting of tigers – and the animals they eat, like deer and wild pigs – continued, while large tracts of their forest habitat became farmland.

India established Project Tiger in 1972 when there were fewer than 2,000 tigers remaining; it is now one of the world’s longest-running conservation programmes. The project aimed to protect and increase tiger numbers by creating reserves from existing protected areas like national parks and wildlife sanctuaries. Part of that process has involved forcing people to relocate.

In protected areas globally, nature conservationists can find themselves at odds with the needs of local communities. Some scientists have argued that, in order for them to thrive, tigers need forests that are completely free of people who might otherwise graze livestock or collect firewood. In a few documented cases, the tiger population has indeed recovered once people were removed from tiger reserves.

But in pitting people against wildlife, relocations foster bigger problems that do not serve the long-term interests of conservation.

India’s relocation policy

Under Project Tiger, 27 tiger reserves were established by 2005, each spanning somewhere between 500 and 2,500 square kilometres. Tiger reserves have a core in which people are prevented from grazing livestock, hunting wildlife and collecting wood, leaves and flowers. A buffer zone encircles this. Here, such activities are allowed, but regulated.About 3,000 families were relocated from these core zones in the first three decades of the project, and from 2005 until 2023, about 22,000 families were moved. Most relocations were involuntary and some plunged those ousted into deeper poverty.

In Sariska tiger reserve in Rajasthan, northwestern India, the first relocation was made during 1976-77. Some of the families returned to the reserve after being given land unsuitable for farming as compensation. This was a poor advertisement for relocation which few other communities opted for voluntarily.

After they were moved from Rajaji tiger reserve in 2012, Gujjar pastoralists who make their living grazing buffalo were prompted to take up farming on new land. With little experience in agriculture, and having been denied their traditional source of income, many struggled to adjust.

The Gujjar did at least gain access to water pumps and electricity. In one case, in the Bhadra tiger reserve in Karnataka, southwestern India, relocation was less painful as people were offered quality agricultural land who already had prior farming experience.

Most people who lost their right to graze livestock or collect forest produce in newly established tiger reserves went on to labour in tea and coffee plantations or factories.

Despite widespread relocations, the tiger population in India continued to plummet, reaching an all-time low of fewer than 1,500 in 2006. Tigers became extinct in Sariska and Panna tiger reserves in 2004 and 2007 respectively.

Local extinction in Sariska prompted the government to enlist the help of tiger biologists and social scientists in 2005. This task force found that illegal hunting of tigers was still happening, their claws, teeth, bones and skin harvested for use in Chinese medicine. Mining and grazing had also continued within many reserves.

Corridors of power

The tiger task force acknowledged that having the local community onside helped prevent illegal hunting and forest fires. The Soliga tribes of Biligiri Rangananthaswamy temple tiger reserve in Karnataka decided not to relocate when offered compensation, but instead took up work rooting out invasive plants like lantana and curbing illegal hunting and timber felling. The Soliga are among the very few communities who have been rewarded with rights in tiger reserves.Similarly, in Parambikulam tiger reserve in Kerala, a state on India’s tropical Malabar coast, communities that were not relocated found work as tour guides and forest guards. People here have supplemented their income by collecting and selling honey, wild gooseberry and medicinal spices, under the joint supervision of the community and forest department officials. Many families have been able to give up cattle rearing as a result, reducing grazing pressure on the forest.

Despite these successes, the government’s policy of relocation remains.

Tiger numbers have recovered to more than 3,000 as of 2022, but Project Tiger shows that relocation alone cannot conserve tigers indefinitely.

A great opportunity awaits. Over 38 million hectares of forest, suitable tiger habitat, lies outside tiger reserves. Declaring these forests “corridors” that allow tigers to move between reserves could reduce the risk of inbreeding and local extinction and reinforce the recovery of India’s tigers.

Studies in certain tiger reserves show that large numbers of villagers would support further relocations if it meant gaining access to drinking water, schools, healthcare and jobs in resettlement sites. A portion of the US$30 million (£22.7 million) spent annually by Project Tiger should be used to make relocations fair. Or better yet, promote the kind of community-based conservation nurtured in the Biligiri Ranganathaswamy temple and Parambikulam tiger reserves.

---

*Dhanapal Govindarajulu is Postgraduate Researcher, Global Development Institute, University of Manchester; Divya Gupta is Assistant Professor, Binghamton University, State University of New York; Ghazala Shahabuddin is Visiting Professor of Environmental Studies, Ashoka University. Source: The Conversation

Comments