By Harsh Thakor*

The Krishnamurti Foundation of America (KFA) lost Roger Edwin Mark Lee, who was a devoted disciple of Jiddu Krishnamurti, one of the greatest and most self realised spiritual philosophers of our time. Mark passed away due to pneumonia complications on April 6, 2024, at he Ventura Community Memorial Hospital in California. His exit was an irreparable loss to the spiritual world.

Mark Lee’s relentless dedication to Krishnamurti and his teachings crystallised the functioning of the Krishnamurti Foundation of America and the wider community of seekers globally. Mark till his last breath manifested the exploration of human consciousness and professed the teachings of Krishnamurti sowing the seeds for inspiring future generations in their seeking understanding and self-discovery.

Mark for a considerable part of his life embraced on the journey to spread Krishnamurti’s basic teaching son ‘Choiceless Awareness’, ‘Limits of Thought’, ‘Pure Energy’, ‘Root of the self and Movement of Thought' ‘De-conditioning Mind’. “Incarnating in Place of Re-incarnation’ etc.

Lee did utmost justice to manifesting Krishnmurti’s virtue that spiritual liberation could be transcended in the very moment, without any rituals, thus in this respect overtaking even Buddha and Christ, and how conventional religions were a barrier to all liberation. He projected how Krishnamurti had in his own right taken spiritual liberation to another zone.

Mark pursued higher education in California, earning a bachelor’s degree in English from California State University, San Francisco, in 1965, followed by a Master’s degree in Education from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1977.

His career, encompassing over four decades, was primarily devoted to the Krishnamurti foundations, where he carried various structural roles including teacher, principal, director, and trustee. His most coveted positions included his time as a teacher and junior school principal from 1965 to 1972 at the Krishnamurti Foundation India’s Rishi Valley School in Andhra Pradesh, India, and as the founding director of the Krishnamurti Foundation of America’s Oak Grove School in Ojai, California, from 1975 to 1985.

In 1986, he was asked by Krishnamurti to take up leadership of the KFA, where he served as the KFA’s executive director for 20 years and as a trustee from 2000 until his death. Mark also served as a trustee of the Krishnamurti Foundation India. Additionally, as director of Krishnamurti Publications, he supervised the editing of several significant works, including the 17-volume “Collected Works of J. Krishnamurti”, “The Book of Life”, and “The Little Book on Living”.

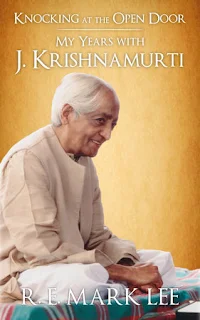

Mark founded Edwin House Publishing, printing memoirs of Krishnamurti’s associates, and himself authored several books on Krishnamurti, including “Knocking at the Open Door: My Years with J. Krishnamurti”; “World Teacher: The Life and Teachings of J. Krishnamurti” and “Probing the Mystery: J. Krishnamurti’s Process”.

The book projects how Krishnamurti spurred his followers to understand or discover themselves by being sensitive, alert, caring, and loving human beings. It dwelled on how he dedicated his life’s purpose to set men absolutely and unconditionally free ,leaving a legacy of an encyclopaedia of teachings that granted no belief system or formula ,no spiritual organisation, no methods, but only symbolising the “truth is a pathless land.”

It covers how Krishnamurti, travelled the globe, challenging violence, corruption, conflict in personal relationships, collapse of moral values, and how man has been enslaved by technology or digital age.

In the chapter ‘Not in India’ Lee traces how Krishnamurti from the start opposed tradition, nationalism and championed concept of one world and his transition within the theosophical society into an international figure. It looks into his rebellion against Hindu and Buddhist rituals. In ‘Waiting for the World Teacher’ Krishnamurti's blooming or genesis into the spiritual path is reflected and his interview on the distinguishing between consciousness and unconsciousness.

‘The Process’ covers how he loved Ojai and the influence it had on shaping his life, be it hiking in the forest, gardening, tending plants and trees, growing vegetables. and interacting with the intellectual community at large. It dwells on how Krishnamurti constructed the school curriculum, and addressed topic of purpose of education, advocating a timeless school and asserting that there was no distinction between academic life and spiritual life. Also, it recounts a mysterious cleansing of Krishnamurti’s brain with no scientific explanation, when meditating, like a divine energy flowing through.

In ‘Private Man,’ he addresses aspect of relationship, and topic on inward and outward relationships. It narrates his evolution from playfulness with women in youth to finding serious people. It dealt with topic of love and sex, illustrating how thinking and image-making are root causes of sexual problems. It also touches on Krishnamurti’s criticism of nationalism and patriotism in the context of armed conflicts and how organised religion bred such conflicts.

In the book ‘The Writer and Teacher’ he describes how Krishnamurti in his notebook maintained a daily record of his perceptions and states of consciousness ,and how it even transcended and surpassed the Upanishads and Vedanta.

In ‘Awakening of Intelligence’ Krishnamurti unravelled that intelligence is not personal, but came into being when the brain discovers its fallibility. He discovered that there is a conflict between knowledge that is required to drive car and experience of knowledge which is the whole movement of the psyche.

In ‘Authority, Organisations and Foundation,’ he analyses the dogmatic nature of religion, how religious beliefs gave a false sense of security. and how organised religion played a divisive role. He expresses his aversion to organisations and authority and insisted that it should never vitiate the institutions.

‘Education and Schools’ reflects on Krishnamurti’s goal to inculcate quality of perception through looking and listening in subjects like maths, science and geometry. Krishnamurti wished students would inculcate free lifelong learning and teachers would have licence to explore inter personal relationships, and roots of conflict, nature of love and compassion etc.

Lee reflects on how when teaching in a Krishnamurti school, he felt an extraordinary sense of freedom, where beauty of insight overshadowed mere content.

In ‘Death and Re-incarnation’ Lee describes the subtle manner in which Krishnamurti made the journey to his heavenly abode, and how his final words were to keep his teachings pure and not to institutionalise them. It quotes Krishnamurti stating that what is important is not the next life but to incarnate in the very moment. Krishnamurti pointed to mysteries in life, but gave no explanation for unravelling them. Something from his very personal being emanated a subtle vibration of peace.

The Krishnamurti Foundation of America (KFA) lost Roger Edwin Mark Lee, who was a devoted disciple of Jiddu Krishnamurti, one of the greatest and most self realised spiritual philosophers of our time. Mark passed away due to pneumonia complications on April 6, 2024, at he Ventura Community Memorial Hospital in California. His exit was an irreparable loss to the spiritual world.

Mark Lee’s relentless dedication to Krishnamurti and his teachings crystallised the functioning of the Krishnamurti Foundation of America and the wider community of seekers globally. Mark till his last breath manifested the exploration of human consciousness and professed the teachings of Krishnamurti sowing the seeds for inspiring future generations in their seeking understanding and self-discovery.

Mark for a considerable part of his life embraced on the journey to spread Krishnamurti’s basic teaching son ‘Choiceless Awareness’, ‘Limits of Thought’, ‘Pure Energy’, ‘Root of the self and Movement of Thought' ‘De-conditioning Mind’. “Incarnating in Place of Re-incarnation’ etc.

Lee did utmost justice to manifesting Krishnmurti’s virtue that spiritual liberation could be transcended in the very moment, without any rituals, thus in this respect overtaking even Buddha and Christ, and how conventional religions were a barrier to all liberation. He projected how Krishnamurti had in his own right taken spiritual liberation to another zone.

Brief life history

Born in Kellogg, Idaho, on August 19, 1940, Mark’s baptism with Krishnamurti began in his teens through the discovery of Krishnamurti’s writings. This paved way to their first in-person meeting in 1965, initiating Mark’s lifelong crusade to investigate Krishnamurti’s work.Mark pursued higher education in California, earning a bachelor’s degree in English from California State University, San Francisco, in 1965, followed by a Master’s degree in Education from the University of California, Santa Barbara, in 1977.

His career, encompassing over four decades, was primarily devoted to the Krishnamurti foundations, where he carried various structural roles including teacher, principal, director, and trustee. His most coveted positions included his time as a teacher and junior school principal from 1965 to 1972 at the Krishnamurti Foundation India’s Rishi Valley School in Andhra Pradesh, India, and as the founding director of the Krishnamurti Foundation of America’s Oak Grove School in Ojai, California, from 1975 to 1985.

In 1986, he was asked by Krishnamurti to take up leadership of the KFA, where he served as the KFA’s executive director for 20 years and as a trustee from 2000 until his death. Mark also served as a trustee of the Krishnamurti Foundation India. Additionally, as director of Krishnamurti Publications, he supervised the editing of several significant works, including the 17-volume “Collected Works of J. Krishnamurti”, “The Book of Life”, and “The Little Book on Living”.

Mark founded Edwin House Publishing, printing memoirs of Krishnamurti’s associates, and himself authored several books on Krishnamurti, including “Knocking at the Open Door: My Years with J. Krishnamurti”; “World Teacher: The Life and Teachings of J. Krishnamurti” and “Probing the Mystery: J. Krishnamurti’s Process”.

On 'World Teacher…'

What os distinctive about this biography is the coverage to the transformation and impact of the life of Krishnmurti in California. The biography is a brief, congeal, readable, commentary giving the younger generation an insight into Krishnamurti’s goals of compassion, love and self-knowledge.The book projects how Krishnamurti spurred his followers to understand or discover themselves by being sensitive, alert, caring, and loving human beings. It dwelled on how he dedicated his life’s purpose to set men absolutely and unconditionally free ,leaving a legacy of an encyclopaedia of teachings that granted no belief system or formula ,no spiritual organisation, no methods, but only symbolising the “truth is a pathless land.”

It covers how Krishnamurti, travelled the globe, challenging violence, corruption, conflict in personal relationships, collapse of moral values, and how man has been enslaved by technology or digital age.

In the chapter ‘Not in India’ Lee traces how Krishnamurti from the start opposed tradition, nationalism and championed concept of one world and his transition within the theosophical society into an international figure. It looks into his rebellion against Hindu and Buddhist rituals. In ‘Waiting for the World Teacher’ Krishnamurti's blooming or genesis into the spiritual path is reflected and his interview on the distinguishing between consciousness and unconsciousness.

‘The Process’ covers how he loved Ojai and the influence it had on shaping his life, be it hiking in the forest, gardening, tending plants and trees, growing vegetables. and interacting with the intellectual community at large. It dwells on how Krishnamurti constructed the school curriculum, and addressed topic of purpose of education, advocating a timeless school and asserting that there was no distinction between academic life and spiritual life. Also, it recounts a mysterious cleansing of Krishnamurti’s brain with no scientific explanation, when meditating, like a divine energy flowing through.

In ‘Private Man,’ he addresses aspect of relationship, and topic on inward and outward relationships. It narrates his evolution from playfulness with women in youth to finding serious people. It dealt with topic of love and sex, illustrating how thinking and image-making are root causes of sexual problems. It also touches on Krishnamurti’s criticism of nationalism and patriotism in the context of armed conflicts and how organised religion bred such conflicts.

In the book ‘The Writer and Teacher’ he describes how Krishnamurti in his notebook maintained a daily record of his perceptions and states of consciousness ,and how it even transcended and surpassed the Upanishads and Vedanta.

In ‘Awakening of Intelligence’ Krishnamurti unravelled that intelligence is not personal, but came into being when the brain discovers its fallibility. He discovered that there is a conflict between knowledge that is required to drive car and experience of knowledge which is the whole movement of the psyche.

In ‘Authority, Organisations and Foundation,’ he analyses the dogmatic nature of religion, how religious beliefs gave a false sense of security. and how organised religion played a divisive role. He expresses his aversion to organisations and authority and insisted that it should never vitiate the institutions.

‘Education and Schools’ reflects on Krishnamurti’s goal to inculcate quality of perception through looking and listening in subjects like maths, science and geometry. Krishnamurti wished students would inculcate free lifelong learning and teachers would have licence to explore inter personal relationships, and roots of conflict, nature of love and compassion etc.

Lee reflects on how when teaching in a Krishnamurti school, he felt an extraordinary sense of freedom, where beauty of insight overshadowed mere content.

In ‘Death and Re-incarnation’ Lee describes the subtle manner in which Krishnamurti made the journey to his heavenly abode, and how his final words were to keep his teachings pure and not to institutionalise them. It quotes Krishnamurti stating that what is important is not the next life but to incarnate in the very moment. Krishnamurti pointed to mysteries in life, but gave no explanation for unravelling them. Something from his very personal being emanated a subtle vibration of peace.

Mark Lee on dialogue

In contemporary times, only Krishnamurti has given to the dialogue a penetrating, non-dogmatic, self-revealing intent. He applied the approach of questioning and inquiry to pave way for truth to unfold itself.He was firm that that no one could transfer truth to another truth. His view suggests true dialogue was penetrating or flowing between the participants. Instead of mere conversation or discussion where listening and understanding are not as important as expressing opinions and winning intellectual points.

In a dialogue participants are encouraged to let facts automatically disclose themselves and to face them without seeking conclusion, through travelling tentatively through thought, allowing logic to elevate the transition beyond logic to a silent understanding. Listening to each other, to oneself speaking and most importantly, watching the content of consciousness, paves way to silence, which is insight.

Lee’s book engulfs continents and cultures. He begins with his own youth in the 1950s as part of California’s laid-back surfer culture; to being personally invited by Krishnamurti to work in India as a teacher of English; and culminates with his return to California, the establishment of the Oak Grove School, and Krishnamurti’s death.

Lee describes Krishnamurti’s thoughts on the nature of true education and how it should inculcate real psychological change; perceive fear and authority; how conditioning harbours racial, religious, ideological, and nationalistic divisions; how the urge to “become someone” nurtures conflict; how overemphasis on the intellect can break personalities; and why teaching is is religious in nature.

Lee’s writing is illustrative, with detailed descriptions of people and places. His projection of India, are mind blowing. His narration of some of Krishnamurti’s strange contradictions in character and behaviour treats the great man as a mere mortal.

Mark Lee has done a great service in gathering all the available material referring to the process which radically transformed Krishnamurti’s whole being. Whatever one can gather from the descriptions, the process, which started in 1922 and continued throughout Krishnamurti’s life, seems to have been unprecedented in human history, as if some mysterious forces were performing surgical operations on various parts of Krishnamurti’s body, especially the brain, causing much pain but bringing great insights.

On one occasion Krishnamurti himself had taken the author to the tree under which the process had taken place. When he asked him about the exact nature of the process, he said, “This is what everyone wants to know. Then they will start imitating it and faking it. No, it cannot be said.” So the mystery remains about the accurate character of the Process and the forces behind it. One result of the Process was an increasing emphasis by Krishnamurti on self-inquiry and self-dependence.

Apparently, he went into each aspect with the teachers and, when he got to seeing, he mentioned the Aborigines in Australia. He explained that it was his understanding that, when the aborigines were in the outback, their senses were very, very sharp and they were aware of everything -- in front of them, behind them, and he reportedly asserted, “I swear, they can even see behind them!”

Krishnamurti then asked, “How can we help our students here at Rishi Valley to see with that kind of awareness?” Mark came up with an idea when every school day morning, some class time was allotted for the students to explore expanding their range of perception with their arms extended horizontally out to their sides. The students and teachers would extend their fingers back out of their range of vision while looking straight ahead and notice when their fingers first came into view.

Initially, the students had to bring their fingers well forward of 180 degrees before they could perceive them while looking straight ahead. After a little practice, however, they were able to notice their extended fingers from a wider field of vision.

---

*Freelance journalist

In a dialogue participants are encouraged to let facts automatically disclose themselves and to face them without seeking conclusion, through travelling tentatively through thought, allowing logic to elevate the transition beyond logic to a silent understanding. Listening to each other, to oneself speaking and most importantly, watching the content of consciousness, paves way to silence, which is insight.

On 'Knocking at the Open Door...'

In “Knocking at the Open Door..”, Mark Lee unravels the historical events, conversations, and memorable interactions they shared. “The goodness and presence of Krishnamurti had a life-changing impact on me and on others who were privileged to be associated with him,” writes Lee, adding that Krishnamurti “lived on the cusp of two worlds: the seen and the unseen,” and “was himself what he taught.”Lee’s book engulfs continents and cultures. He begins with his own youth in the 1950s as part of California’s laid-back surfer culture; to being personally invited by Krishnamurti to work in India as a teacher of English; and culminates with his return to California, the establishment of the Oak Grove School, and Krishnamurti’s death.

Lee describes Krishnamurti’s thoughts on the nature of true education and how it should inculcate real psychological change; perceive fear and authority; how conditioning harbours racial, religious, ideological, and nationalistic divisions; how the urge to “become someone” nurtures conflict; how overemphasis on the intellect can break personalities; and why teaching is is religious in nature.

Lee’s writing is illustrative, with detailed descriptions of people and places. His projection of India, are mind blowing. His narration of some of Krishnamurti’s strange contradictions in character and behaviour treats the great man as a mere mortal.

On ‘Probing the Mystery...’

Throughout his life from 1922 to 1986 Krishnamurti experienced mysterious states of extreme pain, transcendental bliss, and contact with forces unrecognizable to most people. “Probing the Mystery: J. Krishnamurti’s Process” by Mark Lee is a compilation of the full and unedited eyewitness accounts, including his own, of those mysterious and other-worldly states of being. Included are Krishnamurti’s own perceptions on how the conditioned mind turns experience into belief, and assimilates s what is subtle, beautiful, and pure.Mark Lee has done a great service in gathering all the available material referring to the process which radically transformed Krishnamurti’s whole being. Whatever one can gather from the descriptions, the process, which started in 1922 and continued throughout Krishnamurti’s life, seems to have been unprecedented in human history, as if some mysterious forces were performing surgical operations on various parts of Krishnamurti’s body, especially the brain, causing much pain but bringing great insights.

On one occasion Krishnamurti himself had taken the author to the tree under which the process had taken place. When he asked him about the exact nature of the process, he said, “This is what everyone wants to know. Then they will start imitating it and faking it. No, it cannot be said.” So the mystery remains about the accurate character of the Process and the forces behind it. One result of the Process was an increasing emphasis by Krishnamurti on self-inquiry and self-dependence.

Teaching experiment

Mark Lee once shared a very interesting story about Krishnamurti in the late 1960s, when Mark was teaching at Rishi Valley School in India. Krishnamurti conveyed that he wanted the teachers to pay more attention to how the students walked, how they talked, how they looked, and how they listened.Apparently, he went into each aspect with the teachers and, when he got to seeing, he mentioned the Aborigines in Australia. He explained that it was his understanding that, when the aborigines were in the outback, their senses were very, very sharp and they were aware of everything -- in front of them, behind them, and he reportedly asserted, “I swear, they can even see behind them!”

Krishnamurti then asked, “How can we help our students here at Rishi Valley to see with that kind of awareness?” Mark came up with an idea when every school day morning, some class time was allotted for the students to explore expanding their range of perception with their arms extended horizontally out to their sides. The students and teachers would extend their fingers back out of their range of vision while looking straight ahead and notice when their fingers first came into view.

Initially, the students had to bring their fingers well forward of 180 degrees before they could perceive them while looking straight ahead. After a little practice, however, they were able to notice their extended fingers from a wider field of vision.

---

*Freelance journalist

Comments