By Prantik Deka

This is a remarkable story of a man whose extraordinary vision allowed him to see the forest for the trees. Over the span of 40 years, Jadav Payeng has dedicated his life to nurturing and transforming a once barren wasteland in Assam's Jorhat district into a lush green forest reserve teeming with animals, birds and insects of all kinds.

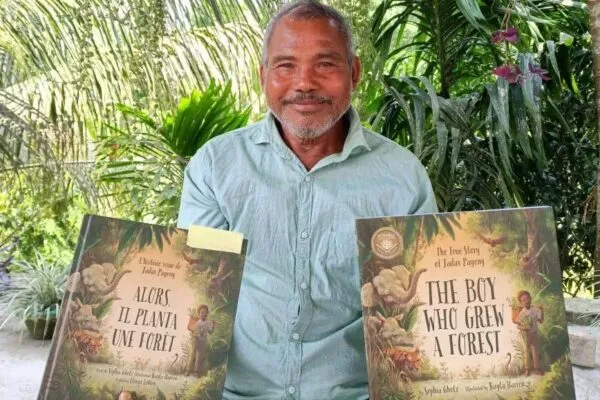

Nicknamed the Forest Man for his extraordinary efforts, Payeng single-handedly built a forest, which is more than one-and-a-half times the size of New York City’s Central Park.

Payeng’s fixation for the land began in 1979, when he was 16, after he saw a large number of snakes that had overheated and died after being washed ashore on a desolated, barren sandbar during a flood. The trees and bushes that normally provide shade and nutrients were washed away as a result of erosion, and so the island’s wildlife was forced to flee.

Many people, whose lands have been lost, were living on embankments for many years or relocated to other safe areas. Many of the important Satras were either swallowed by severe erosion or forced to move off the island. A deeply concerned Payeng took the matter to the forest officials with a request to take immediate and requisite action. But they refused his request to grow trees, and instead suggested that he try growing bamboo, as the bamboo groves on the riverside may serve as a defense against erosion and floods.

And with a lot of patience and persistence, he planted bamboo with a great deal of success. He then planted teak, and other native species such as valcol, arjun, ejar, goldmohur, koroi, moj and himolu, which have thrived and were healthy and vigorous. Many of the trees also possess medicinal values.

At first, planting trees was time-consuming and laborious, until the trees started to grow and then generated their own seeds. He also relocated red ants, earthworms and other insects to the area to improve the soil fertility. Payeng was never weary of planting trees and regenerating his forest. He watered, and he pruned, until he received the results that he longed for. It provided a viable habitat for a lot of rare and endangered species. A lot of migratory birds began flocking to the forest as well.

This is a remarkable story of a man whose extraordinary vision allowed him to see the forest for the trees. Over the span of 40 years, Jadav Payeng has dedicated his life to nurturing and transforming a once barren wasteland in Assam's Jorhat district into a lush green forest reserve teeming with animals, birds and insects of all kinds.

Nicknamed the Forest Man for his extraordinary efforts, Payeng single-handedly built a forest, which is more than one-and-a-half times the size of New York City’s Central Park.

Payeng’s fixation for the land began in 1979, when he was 16, after he saw a large number of snakes that had overheated and died after being washed ashore on a desolated, barren sandbar during a flood. The trees and bushes that normally provide shade and nutrients were washed away as a result of erosion, and so the island’s wildlife was forced to flee.

Many people, whose lands have been lost, were living on embankments for many years or relocated to other safe areas. Many of the important Satras were either swallowed by severe erosion or forced to move off the island. A deeply concerned Payeng took the matter to the forest officials with a request to take immediate and requisite action. But they refused his request to grow trees, and instead suggested that he try growing bamboo, as the bamboo groves on the riverside may serve as a defense against erosion and floods.

And with a lot of patience and persistence, he planted bamboo with a great deal of success. He then planted teak, and other native species such as valcol, arjun, ejar, goldmohur, koroi, moj and himolu, which have thrived and were healthy and vigorous. Many of the trees also possess medicinal values.

At first, planting trees was time-consuming and laborious, until the trees started to grow and then generated their own seeds. He also relocated red ants, earthworms and other insects to the area to improve the soil fertility. Payeng was never weary of planting trees and regenerating his forest. He watered, and he pruned, until he received the results that he longed for. It provided a viable habitat for a lot of rare and endangered species. A lot of migratory birds began flocking to the forest as well.

Today the once harsh environment, spread across 550 hectares (nearly 1,360 acres), has transformed into a lush sanctuary for elephants, deer, apes, wild boars, Asiatic buffalo, a wide variety of reptiles, vultures and many other fascinating species of fauna.

With a missionary zeal, an inspired Jadav Payeng revitalized a barren land, planting tens of thousands of trees that he continues to do so, for over 40 years in the face of insurmountable challenges!

But up until 2009, Payeng’s efforts were largely unknown throughout India and the rest of the world.

Jitu Kalita, a Jorhat-based journalist who writes a popular column on nature in the Assamese magazine “Prantik”, was busy taking photographs of various birds around the Brahmaputra from a hired boat in the autumn of 2007. Everything was normal until he saw vultures and a dense forest around the sandbars, on the far side of Aruna sapori (island).

With a missionary zeal, an inspired Jadav Payeng revitalized a barren land, planting tens of thousands of trees that he continues to do so, for over 40 years in the face of insurmountable challenges!

But up until 2009, Payeng’s efforts were largely unknown throughout India and the rest of the world.

Jitu Kalita, a Jorhat-based journalist who writes a popular column on nature in the Assamese magazine “Prantik”, was busy taking photographs of various birds around the Brahmaputra from a hired boat in the autumn of 2007. Everything was normal until he saw vultures and a dense forest around the sandbars, on the far side of Aruna sapori (island).

"I couldn't believe my eyes," Kalita says in the captivating short film called 'Forest Man'. "I had found a dense forest in the middle of a barren wasteland." On inquiring about it, the boatman told him it was the Molai Forest and even warned him about wild animals.

The intrepid journalist put his own life at risk by going there many times in the next few months, hoping to find the man, who was the creator of a green forest that was once a barren land.

Once, during a regular boat trip to the island, Kalita was staggered to find a man holding a big knife in his hand. He was at his wit's end when that man hurried towards him. Trembling with fear, Kalita tried to hide behind a tree but then he heard a voice.

Sometime back, Payeng had spotted a solitary male wild buffalo taking refuge in the forest. There might even be a herd of them roaming and grazing the forest. Knowing how dangerous it can be, he was quite worried that it might attack the intruder any time.

Kalita recalls his sense of wonder as he first stepped into the forest, which was the densest in the area. Intrigued, he followed the cowherd out, only to discover the biggest story of his life.

After realising that Kalita was a photo-journalist, who had always been deeply interested in nature, Payeng readily entered into a conversation. Payeng struck him as an affable sort of a person.

Kalita was left astounded when Payeng poured out his story.

It is indeed amazing that Payeng's extraordinary mission would have remained largely unknown had it not been for the inquisitiveness of Jitu Kalita, who penned a stirring piece for a local daily, which gained Payeng widespread recognition. Interestingly, Kalita's report, submitted in 2009, was initially withheld by the newspaper editor as some bizarre work of fiction, but relented only after eight months, when the story finally came out.

And based on that very story, the country's leading newspaper – Times of India, allocated a significant space to cover the report, which gained widespread popularity and momentum, even bringing to the notice of the prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Later, JNU invited Payeng and Kalita to attend their seminar on Earth Day. Both Payeng and Kalita were bombarded with queries by the scientists at the seminar, that mostly revolved around the planting of trees and the various methods adopted, before honouring Payeng with ‘The Forest Man of India’ title.

Katita is honoured to have been able to contribute in his own relatively small way to the popularity of Jadav Payeng. Kalita has since accompanied Payeng on every trip, including the one to Evian (France) for the Global Conference for a Sustainable Development in 2012.

“When we received the invitation from France, I told the organisers that we were too poor to travel abroad. But they said they were ready to bear the expenses. They even helped us financially to apply for the passport and the visa,” Kalita said.

The intrepid journalist put his own life at risk by going there many times in the next few months, hoping to find the man, who was the creator of a green forest that was once a barren land.

Once, during a regular boat trip to the island, Kalita was staggered to find a man holding a big knife in his hand. He was at his wit's end when that man hurried towards him. Trembling with fear, Kalita tried to hide behind a tree but then he heard a voice.

Sometime back, Payeng had spotted a solitary male wild buffalo taking refuge in the forest. There might even be a herd of them roaming and grazing the forest. Knowing how dangerous it can be, he was quite worried that it might attack the intruder any time.

Kalita recalls his sense of wonder as he first stepped into the forest, which was the densest in the area. Intrigued, he followed the cowherd out, only to discover the biggest story of his life.

After realising that Kalita was a photo-journalist, who had always been deeply interested in nature, Payeng readily entered into a conversation. Payeng struck him as an affable sort of a person.

Kalita was left astounded when Payeng poured out his story.

It is indeed amazing that Payeng's extraordinary mission would have remained largely unknown had it not been for the inquisitiveness of Jitu Kalita, who penned a stirring piece for a local daily, which gained Payeng widespread recognition. Interestingly, Kalita's report, submitted in 2009, was initially withheld by the newspaper editor as some bizarre work of fiction, but relented only after eight months, when the story finally came out.

And based on that very story, the country's leading newspaper – Times of India, allocated a significant space to cover the report, which gained widespread popularity and momentum, even bringing to the notice of the prestigious Jawaharlal Nehru University (JNU).

Later, JNU invited Payeng and Kalita to attend their seminar on Earth Day. Both Payeng and Kalita were bombarded with queries by the scientists at the seminar, that mostly revolved around the planting of trees and the various methods adopted, before honouring Payeng with ‘The Forest Man of India’ title.

Katita is honoured to have been able to contribute in his own relatively small way to the popularity of Jadav Payeng. Kalita has since accompanied Payeng on every trip, including the one to Evian (France) for the Global Conference for a Sustainable Development in 2012.

“When we received the invitation from France, I told the organisers that we were too poor to travel abroad. But they said they were ready to bear the expenses. They even helped us financially to apply for the passport and the visa,” Kalita said.

Now Kalita’s life revolves around Payeng. He also dons the role of an interpreter when Payeng needs to share his ideas on environmental protection with global audiences at prestigious seminars.

A government employee, Jitu Kalita has done a series of research works on wildlife, including several endangered species. He has also played a vital role in helping police nab a number of poachers and smugglers involved in the smuggling of animal skin and teeth.

A government employee, Jitu Kalita has done a series of research works on wildlife, including several endangered species. He has also played a vital role in helping police nab a number of poachers and smugglers involved in the smuggling of animal skin and teeth.

Former president of India APJ Abdul Kalam officially ordained Payeng with the title 'Forest Man of India'. In 2015, he was honoured with the fourth highest civilian award in India, the Padma Shri. He has been the subject of a number of documentary films, including 'The Molai Forest', a locally made documentary, produced and directed by Jitu Kalita in 2012, the critically acclaimed 'Forest Man' (2013), directed by Canadian filmmaker William Douglas McMaster, which garnered a prize for best documentary at the American Pavilion of the 2014 Cannes Film Festival.

The same year, in 2013, documentary filmmaker Aarti Shrivastava captured his selfless work in the documentary film titled 'Foresting Life'. Kolkata-based filmmaker Tamal Dasgupta's documentary 'Soul of the Forest' (2014), went on to receive several national and international awards.

Today at 63, this compassionate environmentalist is every bit as passionate about his forest, despite impending environmental and human dangers. There are concerns, as expressed by scientists, that Payeng's forest, located on Majuli Island, in the middle of the Brahmaputra River, could well be submerged in the next 20 years, thanks to the recurring erosion which is eating away large chunks of land. At 1,200 square kilometres, Majuli was once considered the world's biggest river island, but today, it is slowly shrinking due to the river's wrath, and is reduced to just 400 square kilometres.

The tree roots help to physically bind the soil and absorb large amounts of water, reducing erosion from flooding, and Payeng believes natural methods will be more effective in the years to come than following government flood prevention schemes.

The forest and it's abundance has created a fertile ground for smugglers and poachers. Human encroachment for economic gain has always been nibbling away at the edges, which consumes Payeng with a lot of worry.

Payeng has been unsparing in his criticism of those who ruthlessly exploit nature. The most important direct negative impacts on biodiversity are habitat destruction.

Jadav Payeng’s work has been credited for significantly helping to fortify Majuli, also a cradle of Assamese culture. The uniqueness of the place and the interests that it's future entails has fostered numerous and diverse research projects over the years. The local governments, over the years, have tried to get the island listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, but their applications have been rejected.

As a gesture of gratitude to Payeng's enormous effort and dedication to the land, the government of Assam named the forest after him. It's called Molai Kathoni (Molai's woods), after Payeng's nickname, Molai, which is located near Kokilamukh, in Jorhat.

"My dream is to fill Majuli Island and Jorhat with forest again," Payeng, who has given up everything to live a life in isolation, tells us in 'Forest Man'. "I will continue to plant till my last breath. I tell those people that cutting those trees will not get you anything. Cut me before you cut my trees.

“They said they were ready to bear the expenses. They even helped us financially to apply for the passport and the visa,” Kalita said.

Now Kalita’s life revolves around Payeng. He also dons the role of an interpreter when Payeng needs to share his ideas on environmental protection with global audiences at prestigious seminars.

When I asked Payeng about his thoughts on protecting the environment, he came up with the simplest of solutions.

Today at 63, this compassionate environmentalist is every bit as passionate about his forest, despite impending environmental and human dangers. There are concerns, as expressed by scientists, that Payeng's forest, located on Majuli Island, in the middle of the Brahmaputra River, could well be submerged in the next 20 years, thanks to the recurring erosion which is eating away large chunks of land. At 1,200 square kilometres, Majuli was once considered the world's biggest river island, but today, it is slowly shrinking due to the river's wrath, and is reduced to just 400 square kilometres.

The tree roots help to physically bind the soil and absorb large amounts of water, reducing erosion from flooding, and Payeng believes natural methods will be more effective in the years to come than following government flood prevention schemes.

The forest and it's abundance has created a fertile ground for smugglers and poachers. Human encroachment for economic gain has always been nibbling away at the edges, which consumes Payeng with a lot of worry.

Payeng has been unsparing in his criticism of those who ruthlessly exploit nature. The most important direct negative impacts on biodiversity are habitat destruction.

Jadav Payeng’s work has been credited for significantly helping to fortify Majuli, also a cradle of Assamese culture. The uniqueness of the place and the interests that it's future entails has fostered numerous and diverse research projects over the years. The local governments, over the years, have tried to get the island listed as a UNESCO World Heritage site, but their applications have been rejected.

As a gesture of gratitude to Payeng's enormous effort and dedication to the land, the government of Assam named the forest after him. It's called Molai Kathoni (Molai's woods), after Payeng's nickname, Molai, which is located near Kokilamukh, in Jorhat.

"My dream is to fill Majuli Island and Jorhat with forest again," Payeng, who has given up everything to live a life in isolation, tells us in 'Forest Man'. "I will continue to plant till my last breath. I tell those people that cutting those trees will not get you anything. Cut me before you cut my trees.

“They said they were ready to bear the expenses. They even helped us financially to apply for the passport and the visa,” Kalita said.

Now Kalita’s life revolves around Payeng. He also dons the role of an interpreter when Payeng needs to share his ideas on environmental protection with global audiences at prestigious seminars.

When I asked Payeng about his thoughts on protecting the environment, he came up with the simplest of solutions.

“It’s not a difficult task. Make environmental science a compulsory subject in primary school and encourage kids to plant trees. Today global warming is threatening our very existence because the man has always used nature as his slave. So we need to teach the kids the value of trees. Only then will they love trees,” says Payeng who feels Sanjeev (11), his youngest son, is already in love with nature. And he hopes that the boy will keep his forest alive.

As I was about to say goodbye to this remarkable man, his mobile rang and he was like, ‘Yes, it’s Jadav Payeng here. No, Molai is my pet name. Okay, thank you. Yes, yes I will.’

I thought it was just an ordinary phone conversation until he turned around and his face broke into the most beautiful smile. He spells out the antidote for man’s ills: a compassionate revolution to pull up the fences and restore the balance of mankind.

As I was about to say goodbye to this remarkable man, his mobile rang and he was like, ‘Yes, it’s Jadav Payeng here. No, Molai is my pet name. Okay, thank you. Yes, yes I will.’

I thought it was just an ordinary phone conversation until he turned around and his face broke into the most beautiful smile. He spells out the antidote for man’s ills: a compassionate revolution to pull up the fences and restore the balance of mankind.

Comments