By Harsh Thakor

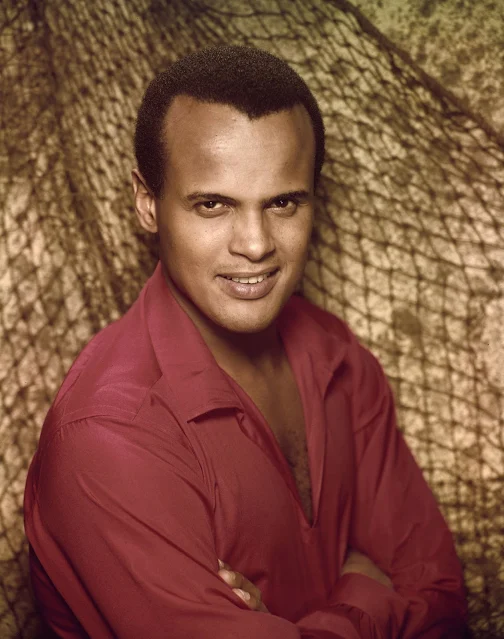

The outstanding Jamaica-born artist, Civil Rights activist and internationalist, Harry Belafonte, died from congestive heart failure at age 96, a week ago, on April 25, 2023.A mascot of people’s emancipation from injustice. His life story or events that shaped his life are amongst the most gripping commentaries ever.

Belafonte achieved gigantic fame almost 70 years ago, when he was only in his mid-20s. He popularized calypso music in the US, with a hugely successful concert and recording career in several different musical genres. His album Calypso (1956) became the first long-playing record to sell 1 million copies in a single year.

For the major part of his long life, Belafonte classed himself first and foremost a social and political activist, not a singer or actor. Few progressive or radical artists were such powerhouses of talent or endowed with such extraordinary natural gifts. Rare in history to have witnessed musicians of actors transcending spirit of liberation or struggle to emancipate humanity at such a scale. His political speeches stirred the souls of people, more than the power with which his voice pulled crowds.

The singer also went on to appear as a screen actor, including in a well-known role opposite Dorothy Dandridge in Otto Preminger’s ground-breaking, all-black Carmen Jones (1959), as well as major roles in Island in the Sun (Robert Rossen, 1957) and Odds Against Tomorrow (Robert Wise, 1959). In the 1960s, however, Belafonte largely parted away from a career in Hollywood, complaining that the film studios were not interested in promoting socially conscious films he was searching for. He appeared in some later films, notably co-starring with Zero Mostel in The Angel Levine (1970) and appearing in several Robert Altman films in the 1990s: The Player (1992) and Kansas City (1996).

Despite becoming the first Black person to win a TV Emmy award in 1960, a Broadway Tony award in 1954 and selling millions of recordings, Belafonte experienced racist discrimination firsthand, like most Black entertainers in the 1950s and 1960s, including his good friend, the late actor Sidney Poitier. Belafonte played a role of an important political organizer and financial backer of the Civil Rights Movement led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

In a speech before the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade/Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives meeting in New York City on April 27, 1997, Belafonte, a survivor of the witch hunt, stated, “And it was from Paul that I learned that the purpose of art is not just to show life as it is, but to show life as it should be. And that if art were put into the service of the human family, it could only enhance their betterment.”

“Paul said to me, ‘Harry, get them to sing your song, and they will want to know who you are. And if they want to know who you are, you’ve gained the first step in bringing truth and bringing insight that might help people get through this rather difficult world.’”

Belafonte ended his speech this way: “Thank you — and long live the Brigade and what it stands for — and long live each and every one of you — and give up smoking! Fidel Castro gave it up, you can give it up!” (University of Chicago)

Belafonte left no stone unturned in offering moral support for a just trial for the revolutionary journalist and African American political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Belafonte first met Martin Luther King Jr. in 1956, in the midst of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Both men, not yet 30 years old, had already become famous in their respective fields. The singer and civil rights leader immediately forged a bond, and Belafonte went on to help raise funds for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and to develop a strong collaborative friendship with King. When King was in New York, he and his closest advisers—Belafonte among them—often met at the singer’s apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. No other entertainer immersed themselves in the very heart of the Civil Rights Movement, in the depth of Belafonte.

Belafonte told Chavez during a TV and radio broadcast: “No matter what the greatest tyrant in the world, the greatest terrorist in the world, George W. Bush says, we’re here to tell you: Not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of the American people … support your revolution. . . . We respect you, admire you, and we are expressing our full solidarity with the Venezuelan people and your revolution.” (jamaicaobserver.com. Jan. 9, 2006)

On the 95th birthday of the U.S. actor, musician and social activist — born March 1, 1927, in New York — Belafonte continues to be a source of inspiration for many of his compatriots and for those of us who appreciate him as an exceptional artist, extraordinary human being and dear friend. One name cannot be overlooked in describing the development of such a special bond: Fidel Castro. The historic leader of the revolution and the actor and singer, a companion of Martin Luther King in the struggle, cultivated a very close relationship, after Belafonte reencountered Cuba in 1979, subsequently never foregoing his trips to Havana, as long as his health allowed.

Belafonte got to know the city in the 1950s, not without first exchanging words and experiences with many Cubans living in New York, and feeling an affinity for the music of the neighboring country, especially after listening to Chano Pozo with Dizzy Gillespie’s band.

In those same years, more than sensation of his films, the song “Matilda, Matilda” touched the core of the soul of the Cubans at that time, a song that dates back at least to the 1930s, when the calypso pioneer, Trinidad’s King Radio (aka Norman Span) released the song. Belafonte first recorded it in 1953, and it turned into immediate hit, further popularized with its inclusion on his second full-length album with RCA Victor in 1955.

In his memoirs, “My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race, and Defiance”, published in 2011, its Spanish version still unpublished in Cuba, he wrote: “When I became an artist and began to have some celebrity, I went to Cuba quite regularly, before ’59. I went there with Sammy Davis Jr., and to hear Nat King Cole, and to hang out with Frank Sinatra; the place where we most often gathered was the Hotel National.

“Everybody was performing there except me. When they came to me — and I had a work contract, when the Habana Riviera Hotel first opened — I was in an interracial marriage, as it was called in those days, and suddenly I became a persona non grata, in Cuba, everywhere.

Right around that time he filmed Robert Rossen’s film, “Island In The Sun,” in which he was cast as a Black union leader in a fictitious West Indian country who lived a love story with a young white woman from the upper middle class (Joan Fontaine). The film ignited controversy when it was released in the United States in 1957, considering that racist elites considered its content an irresponsible transgression.

After the triumph of the Cuban Revolution on January 1, 1959, Fidel, who, in addition to being an avid reader, enjoyed movies to the extent that his political and governmental responsibilities allowed, saw the film and talked about it with Belafonte, along with his wife Julie, and Sidney Poitier, a friend and colleague. For both Fidel and Harry, racism and discrimination based on skin colour were and intolerable cultural phenomena.

In this regard, Belafonte noted in his memoirs: “Many Cuban exiles say that in Cuba there was no racism before the Revolution, that Cuba was never racist, never like the United States. I think that Cuba, among all the Caribbean islands, all with racist practices, was the most racist . . .

“So, when I went to Cuba after the revolution, the first thing I noticed was the mixture of people, particularly among young people, there were still residues of the old customs, but certainly among the young, when I went to the university, and when I went to cultural sites, when I went to day care centers, wherever I went in Cuba among the young, I was deeply impressed by the extent of racial integration . . . . I am not suggesting that in Cuba there is no racism, but it is important to know that it is not an official state practice, nor is it institutionalized.”

The objective and subjective factors that leaned towards the resurrection of racist and discriminatory attitudes in Cuban life, and the struggle to erase them as an integral part of the Cuban revolutionary project, were the subjects of Belafonte’s conversations with Fidel more than once, and over the last two years, he has followed news of the implementation of our “National Program Against Racism and Racial Discrimination,” an effort inspired by Fidel’s ideas.

His unflinching solidarity and sense of justice, was illustrated in the manner with which he introduced a rally held at the Church of Reconciliation in New York on September 27, 2003. On that day he offered prayers for the five Cuban anti-terrorist heroes serving long prison sentences in the United States.

He [Belafonte] stated:, “What is happening with our policy toward Cuba is not the American way, it is not the true voice of the American people, it is not the true voice of those of us who believe deeply, profoundly, in the rights of all peoples, and the freedom of all people and in democracy…There is a great deal that the Cuban government, the Cuban people have achieved, that many of us here are still attempting to achieve.”

Belafonte was once asked why he supports the Cuban people, and he stated, “I don’t see it as a supreme effort. It is a way of life: if you believe in freedom, if you believe in justice, if you believe in democracy, if you believe in people’s rights, if you believe in the harmony of all humanity.”

In Belafonte’s case, this was also entangled with an emphasis on race, and on support for nationalist opponents of US imperialism, such as Cuba’s Fidel Castro and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez. While he did not welcome the rhetoric of the black nationalists or identity politics fanatics, he distinguished the struggle against racism from the challenges facing the working class as a whole. This originated from his whole reformist outlook, rekindled by the experience of the postwar boom. He dismissed the role of the working class in the fight for socialism.

New York Times columnist Charles Blow, in his column this week paying tribute to Belafonte, quotes the entertainer at a speech he gave before an audience at the Ford Foundation 10 years ago. “We surrendered to greed,” said Belafonte. “We surrendered to our hedonist joys. We destroyed the civil rights movement. Looking at the great harvest of achievements we had, all the young men and women of our communities ran off to the feast of Wall Street and big business and opportunity.”

Belafonte targets himself when he makes criticisms like these, as one of the most famous of the cream of American radicals, and not only African Americans, of course. It was this cream that reconciled with capitalism. Belafonte was shaken by this development. He could maintain complete silence; he could not be part of celebrations of Wall Street and the betrayal of the mass struggles of the 1950s and ’60s. Still, he had no alternative to offer, and joined hands with capitalist politicians, from John F. Kennedy to Obama and Bernie Sanders.

When King was assassinated, Belafonte stated that he quickly decided, after King’s death, to “help elect black candidates at every level of the political system… I helped persuade Andy Young to run for Congress in Georgia, gave him money, and staged a lot of free concerts.” Belafonte made “four- and five-figure contributions” to help elect black mayors in Cleveland; Gary, Indiana, and other cities. Where King had called to extinguish the “burning house” of capitalism, his followers took the opposite recourse.

---

Harsh Thakor is a freelance journalist who has done extensive research on progressive artists .Owes gratitude to information from ‘Workers World ‘ and ‘World Socialist' website.

The outstanding Jamaica-born artist, Civil Rights activist and internationalist, Harry Belafonte, died from congestive heart failure at age 96, a week ago, on April 25, 2023.A mascot of people’s emancipation from injustice. His life story or events that shaped his life are amongst the most gripping commentaries ever.

Belafonte achieved gigantic fame almost 70 years ago, when he was only in his mid-20s. He popularized calypso music in the US, with a hugely successful concert and recording career in several different musical genres. His album Calypso (1956) became the first long-playing record to sell 1 million copies in a single year.

For the major part of his long life, Belafonte classed himself first and foremost a social and political activist, not a singer or actor. Few progressive or radical artists were such powerhouses of talent or endowed with such extraordinary natural gifts. Rare in history to have witnessed musicians of actors transcending spirit of liberation or struggle to emancipate humanity at such a scale. His political speeches stirred the souls of people, more than the power with which his voice pulled crowds.

The singer also went on to appear as a screen actor, including in a well-known role opposite Dorothy Dandridge in Otto Preminger’s ground-breaking, all-black Carmen Jones (1959), as well as major roles in Island in the Sun (Robert Rossen, 1957) and Odds Against Tomorrow (Robert Wise, 1959). In the 1960s, however, Belafonte largely parted away from a career in Hollywood, complaining that the film studios were not interested in promoting socially conscious films he was searching for. He appeared in some later films, notably co-starring with Zero Mostel in The Angel Levine (1970) and appearing in several Robert Altman films in the 1990s: The Player (1992) and Kansas City (1996).

Background

Belafonte was born into a West Indian family in Harlem, although he spent part of his boyhood in Jamaica. After the Second World War, he met Sidney Poitier at the American Negro Theater and took acting classes at The New School under left-wing German theatre director Erwin Piscator. Belafonte traveled in left-wing circles around the Communist Party. He met actors Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee and singer Paul Robeson, whom he called a mentor.Despite becoming the first Black person to win a TV Emmy award in 1960, a Broadway Tony award in 1954 and selling millions of recordings, Belafonte experienced racist discrimination firsthand, like most Black entertainers in the 1950s and 1960s, including his good friend, the late actor Sidney Poitier. Belafonte played a role of an important political organizer and financial backer of the Civil Rights Movement led by Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.

Impact of Paul Robeson on his life

Belafonte drew his lifelong inspiration personally and politically by the great singer and radical actor, Paul Robeson, who was a victim of the anti-communist, McCarthyite witch hunt that all but reduced him to dust.In a speech before the Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade/Abraham Lincoln Brigade Archives meeting in New York City on April 27, 1997, Belafonte, a survivor of the witch hunt, stated, “And it was from Paul that I learned that the purpose of art is not just to show life as it is, but to show life as it should be. And that if art were put into the service of the human family, it could only enhance their betterment.”

“Paul said to me, ‘Harry, get them to sing your song, and they will want to know who you are. And if they want to know who you are, you’ve gained the first step in bringing truth and bringing insight that might help people get through this rather difficult world.’”

Belafonte ended his speech this way: “Thank you — and long live the Brigade and what it stands for — and long live each and every one of you — and give up smoking! Fidel Castro gave it up, you can give it up!” (University of Chicago)

Belafonte left no stone unturned in offering moral support for a just trial for the revolutionary journalist and African American political prisoner Mumia Abu-Jamal.

Support to Martin Luther King

Belafonte’s collaboration with and steadfast support for Martin Luther King Jr. is the political connection for which he is most well-known. The singer financially supported King and his family, including after King was assassinated in 1968. He bailed out King and others when they were jailed. He turned his spacious home on Manhattan’s Upper West Side into a virtual second home and unofficial office for the civil rights leader when he was in New York. It was in this apartment that the historically significant meeting dominated by a sharp exchange between King and Andrew Young, and referenced by Belafonte in his memoir, took place.Belafonte first met Martin Luther King Jr. in 1956, in the midst of the Montgomery Bus Boycott. Both men, not yet 30 years old, had already become famous in their respective fields. The singer and civil rights leader immediately forged a bond, and Belafonte went on to help raise funds for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference and to develop a strong collaborative friendship with King. When King was in New York, he and his closest advisers—Belafonte among them—often met at the singer’s apartment on Manhattan’s Upper West Side. No other entertainer immersed themselves in the very heart of the Civil Rights Movement, in the depth of Belafonte.

Challenging racism

Belafonte was an important U.S. spokesperson for the anti-apartheid struggle in South Africa. Belafonte whole heartedly supported left-wing progressive causes that threw a challenge to the racist, white status quo; this includes being a vocal opponent of imperialist war. In January 2006, Belafonte led a delegation, which included actor Danny Glover, farmworker organizer Dolores Huerta and professor Cornel West, to Caracas, Venezuela, to meet with the late President Hugo Chavez.Belafonte told Chavez during a TV and radio broadcast: “No matter what the greatest tyrant in the world, the greatest terrorist in the world, George W. Bush says, we’re here to tell you: Not hundreds, not thousands, but millions of the American people … support your revolution. . . . We respect you, admire you, and we are expressing our full solidarity with the Venezuelan people and your revolution.” (jamaicaobserver.com. Jan. 9, 2006)

Supporter of the Cuban Revolution

Belafonte was Cuba’s Friendship Medal by the Council of State in 2020. When on July 23, 2020, Harry Belafonte held aloft the Friendship Medal, awarded by the Cuban state, traversing his mind, was a recollection of an unforgettable chain of events during his life when he shared the same luck, convictions and destiny of inhabitants of Cuba. On that day, then Cuban ambassador in Washington José R. Cabañas stated:, “This distinction serves as recognition of your lifelong solidarity with Cuba, your respect and admiration for the Cuban revolutionary process.”On the 95th birthday of the U.S. actor, musician and social activist — born March 1, 1927, in New York — Belafonte continues to be a source of inspiration for many of his compatriots and for those of us who appreciate him as an exceptional artist, extraordinary human being and dear friend. One name cannot be overlooked in describing the development of such a special bond: Fidel Castro. The historic leader of the revolution and the actor and singer, a companion of Martin Luther King in the struggle, cultivated a very close relationship, after Belafonte reencountered Cuba in 1979, subsequently never foregoing his trips to Havana, as long as his health allowed.

Belafonte got to know the city in the 1950s, not without first exchanging words and experiences with many Cubans living in New York, and feeling an affinity for the music of the neighboring country, especially after listening to Chano Pozo with Dizzy Gillespie’s band.

In those same years, more than sensation of his films, the song “Matilda, Matilda” touched the core of the soul of the Cubans at that time, a song that dates back at least to the 1930s, when the calypso pioneer, Trinidad’s King Radio (aka Norman Span) released the song. Belafonte first recorded it in 1953, and it turned into immediate hit, further popularized with its inclusion on his second full-length album with RCA Victor in 1955.

In his memoirs, “My Song: A Memoir of Art, Race, and Defiance”, published in 2011, its Spanish version still unpublished in Cuba, he wrote: “When I became an artist and began to have some celebrity, I went to Cuba quite regularly, before ’59. I went there with Sammy Davis Jr., and to hear Nat King Cole, and to hang out with Frank Sinatra; the place where we most often gathered was the Hotel National.

“Everybody was performing there except me. When they came to me — and I had a work contract, when the Habana Riviera Hotel first opened — I was in an interracial marriage, as it was called in those days, and suddenly I became a persona non grata, in Cuba, everywhere.

Right around that time he filmed Robert Rossen’s film, “Island In The Sun,” in which he was cast as a Black union leader in a fictitious West Indian country who lived a love story with a young white woman from the upper middle class (Joan Fontaine). The film ignited controversy when it was released in the United States in 1957, considering that racist elites considered its content an irresponsible transgression.

After the triumph of the Cuban Revolution on January 1, 1959, Fidel, who, in addition to being an avid reader, enjoyed movies to the extent that his political and governmental responsibilities allowed, saw the film and talked about it with Belafonte, along with his wife Julie, and Sidney Poitier, a friend and colleague. For both Fidel and Harry, racism and discrimination based on skin colour were and intolerable cultural phenomena.

In this regard, Belafonte noted in his memoirs: “Many Cuban exiles say that in Cuba there was no racism before the Revolution, that Cuba was never racist, never like the United States. I think that Cuba, among all the Caribbean islands, all with racist practices, was the most racist . . .

“So, when I went to Cuba after the revolution, the first thing I noticed was the mixture of people, particularly among young people, there were still residues of the old customs, but certainly among the young, when I went to the university, and when I went to cultural sites, when I went to day care centers, wherever I went in Cuba among the young, I was deeply impressed by the extent of racial integration . . . . I am not suggesting that in Cuba there is no racism, but it is important to know that it is not an official state practice, nor is it institutionalized.”

The objective and subjective factors that leaned towards the resurrection of racist and discriminatory attitudes in Cuban life, and the struggle to erase them as an integral part of the Cuban revolutionary project, were the subjects of Belafonte’s conversations with Fidel more than once, and over the last two years, he has followed news of the implementation of our “National Program Against Racism and Racial Discrimination,” an effort inspired by Fidel’s ideas.

His unflinching solidarity and sense of justice, was illustrated in the manner with which he introduced a rally held at the Church of Reconciliation in New York on September 27, 2003. On that day he offered prayers for the five Cuban anti-terrorist heroes serving long prison sentences in the United States.

He [Belafonte] stated:, “What is happening with our policy toward Cuba is not the American way, it is not the true voice of the American people, it is not the true voice of those of us who believe deeply, profoundly, in the rights of all peoples, and the freedom of all people and in democracy…There is a great deal that the Cuban government, the Cuban people have achieved, that many of us here are still attempting to achieve.”

Belafonte was once asked why he supports the Cuban people, and he stated, “I don’t see it as a supreme effort. It is a way of life: if you believe in freedom, if you believe in justice, if you believe in democracy, if you believe in people’s rights, if you believe in the harmony of all humanity.”

Weaknesses

Belafonte’s first political influences, in Stalinist circles, shaped his conversion toward Popular Front reformism, including the claim that the Democratic Party could be pushed to the left and could garner benefits for the working class. It was in this spirit that Belafonte supported the presidential campaigns of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders.In Belafonte’s case, this was also entangled with an emphasis on race, and on support for nationalist opponents of US imperialism, such as Cuba’s Fidel Castro and Venezuela’s Hugo Chavez. While he did not welcome the rhetoric of the black nationalists or identity politics fanatics, he distinguished the struggle against racism from the challenges facing the working class as a whole. This originated from his whole reformist outlook, rekindled by the experience of the postwar boom. He dismissed the role of the working class in the fight for socialism.

New York Times columnist Charles Blow, in his column this week paying tribute to Belafonte, quotes the entertainer at a speech he gave before an audience at the Ford Foundation 10 years ago. “We surrendered to greed,” said Belafonte. “We surrendered to our hedonist joys. We destroyed the civil rights movement. Looking at the great harvest of achievements we had, all the young men and women of our communities ran off to the feast of Wall Street and big business and opportunity.”

Belafonte targets himself when he makes criticisms like these, as one of the most famous of the cream of American radicals, and not only African Americans, of course. It was this cream that reconciled with capitalism. Belafonte was shaken by this development. He could maintain complete silence; he could not be part of celebrations of Wall Street and the betrayal of the mass struggles of the 1950s and ’60s. Still, he had no alternative to offer, and joined hands with capitalist politicians, from John F. Kennedy to Obama and Bernie Sanders.

When King was assassinated, Belafonte stated that he quickly decided, after King’s death, to “help elect black candidates at every level of the political system… I helped persuade Andy Young to run for Congress in Georgia, gave him money, and staged a lot of free concerts.” Belafonte made “four- and five-figure contributions” to help elect black mayors in Cleveland; Gary, Indiana, and other cities. Where King had called to extinguish the “burning house” of capitalism, his followers took the opposite recourse.

Conclusion

It is complex to analyse the phenomena that ultimately make Belafonte draw away from Marxism or a Communist party and be entrapped in the quagmire of capitalist circles. Still we should applaud him for against all odds withstanding counter-revolutionary tides, relentlessly backing progressive regimes of Cuba and Venezuela, speaking out against the Iraq War and apartheid in South Africa earlier ,ridiculing a tyrant like Donald Truump and delivering a death defying blow to racism. .His very character was manifestation of the spirit of liberation from the shackles of oppression and few ever as touched the very core of the soul of the oppressed. Regretful that unlike Paul Robeson Harry could not champion Marxism , Socialism and Contribution of Mao Tse Tung or integrate with the radical black revolutionary movements like the black Panthers or militants like Malcolm X , but overall his positive impact overshadowed the negative art. Arguable it was the very weakness of the progressive Marxist forces that were unable to win over such an icon. It is vital that his likes are re-born in the world in the era of globalisation with oppression on an unparalleled scale, and most artists dancing it it’s tune, worldwide.---

Harsh Thakor is a freelance journalist who has done extensive research on progressive artists .Owes gratitude to information from ‘Workers World ‘ and ‘World Socialist' website.

Comments