By Arjun Kumar, Anshula Mehta, Simi Mehta, Kuldeep Singh

As per the Pattern of Assistance under NPCBVI for 2017-20, outlined by MoHFW in 2018, the programme is part of the Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) Flexible Pool under the NHM. Funds for implementation of the programme are released by NHM as grant-in-aid into the NPCBVI account, through the respective State Health Societies. The major activities for which grants-in-aid are provided are cataract operations, treatment/management of other eye diseases, distribution of free spectacles to school children (to District Health Societies (DHSs), eye banks and eye donation centres, training of paramedical ophthalmic assistants (PMOAs) and other paramedics, maintenance of ophthalmic equipment, district and sub-district hospitals and vision centres, Information Education Communication (IEC), and contractual manpower, among others. NGOs and private practitioners are reimbursed for cataract operations, and assistance is provided for the Government sector. Apart from this, other eye care services are also covered under Ayushman Bharat and various state governments have also designed their schemes, e.g., Chokher Alo (West Bengal), Cataract-Blindness Free Gujarat, Kanti Velugu (Telangana) and Dr. YSR Kanti Velugu (Andhra Pradesh), among others.

The Quarterly Review of the Programme (September 2019) lists its objectives and highlights major issues as follows:

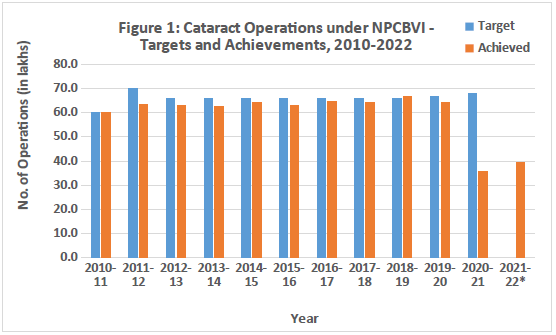

Over time, the programme has maintained a phenomenal pace in achieving its targets for cataract operations. However, the target set at national level are far from actual need of the cataract operation needed. Further, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the programme performance has seen a decline. In light the backlog of cataract surgeries and the government’s push to clear it, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India has notified a special campaign ‘Rashtriya Netra Jyoti Abhiyan’ in May 2022 (vide D.O.No.T.12020/10/2022-NCD-1/NPCB&VI dated 18th May 2022) with a proposed total of 270 lakh cataract surgeries to be carried out over the next three financial years (2022-23 to 2024-25), various media reports in recent times has also covered and carried out governments’ ambition and plans for the same. This aim to increase the cataract surgeries by 17% in FY22-23, 40% in FY 23-24 and 63% in FY 24-25 without any additional investment in surgical infrastructure, human resource, training or by providing direct budgetary incentive to state or districts under Rashtriya Netra Jyoti Abhiyan.

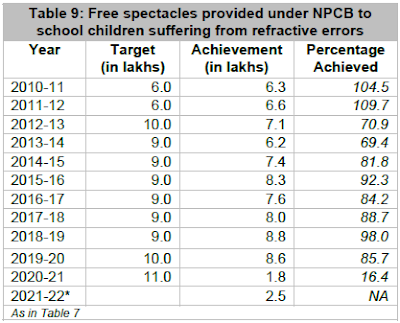

Similarly, other programme activities – provision of free spectacles to school children suffering from refractive errors, treatment and management of other eye diseases, collection of donated eyes, and training of eye surgeons – have been carried out at a rapid pace over the years, but have seen a dip amid the pandemic. The International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness estimates 265.8 million people in India with visual impairment, which is highest in the world. However, the existing efforts for refractive errors screening and providing spectacles are limited to a very small part of the total target group, including children in schools.

Further, a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare [One Hundred and Twenty-Sixth Report on Demands for Grants 2021-22 (Demand No. 44) of the Department of Health and Family Welfare] in March 2021 noted that there had been underutilisation of funds earmarked for the purposes of capacity building of personnel, which requires attention.

As highlighted in Table 13, a cursory look at the expenditure of the NPCBVI suggests the backlog and impact of COVID-19 on the financial aspects. The total expenditure for the FY 2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21 was ₹ 396.8, 331.6 and 227.4 crore respectively. Moreover, the approval of expenditure for FY 2021-22 was increased to a whopping ₹ 724 crore, nonetheless, owing to the second and third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021-22, the utilisation has been a mere ₹ 140.5 crore, or around one-fifth of the approved expenditure. There are also statewise variations in the achievement levels as elucidated in Table 13. Thus, there is an urgent need to reinvigorate NPCBVI and the eye care sector by the Central and State Governments, having unmet target demands and unspent funds.

Accessibility continues to be a roadblock in moving towards universal eye care. Primary health care needs to be strengthened through an extensive health workforce, setting up of more PHCs and Vision Centres (VCs) and the provision of teleophthalmology, Multipurpose District Mobile Ophthalmic Units in District Hospitals, and the added participation of private and other voluntary players, among others.

It is important to add that NPCBVI, too, seeks to secure participation of voluntary and private organisations to expand the provision of eye care services. However, concerns regarding administrative and logistical glitches, and delays in payments to these organisations remain a roadblock in strengthening the reach and achievement of the programme.

Newer and diverse challenges have emerged in the recent years. The available data on vision loss and eye care is, for the major part, programme related. There is a dearth of overall data on the eye care sector, especially from the private and NGO sector to arrive at a complete picture. While data on eye care and metrics on programme achievements are available from various official sources, there is a need for centralised real-time availability of eye care statistics from all sources. A component of this challenge also lies in the quality of eye care data supplied at the primary level by states. Moving ahead, initiatives such as Digital India and Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission must take the lead in integrating health records on a real-time basis.

The COVID-19 pandemic poses challenges for reaching the population and implementation of initiatives. Digitalization of eye care services – via IEC messages and delivery of preliminary diagnoses via teleopthalmology in areas with difficult terrain, in part, may assist efforts towards awareness and coverage. The Medical Council of India has come up with a ‘Telemedicine Practice Guidelines for Enabling Registered Medical Practitioners to Provide Healthcare Using Telemedicine’ in 2020, which is a welcome step to address the access and human resources challenge. However, deployment of tele-opthalmology is critically dependent on technology, hardware infrastructure and connectivity to ensure the patent and registered medical provider’s Identification, mode of Communication, Consent of patient, consultation process, patient Evaluation and Patient Management process post evaluation and follow-up.

Prioritizing children’s eye health, in light of the pandemic-induced online teaching-learning process, is of utmost importance. Existing initiatives of school eye screenings and provision of free spectacles to children with refractive errors must be rigorously continued, and coverage expanded as per the evolving pandemic situation. COVID- and lockdown-induced emerging dimensions to children’s – as well as other age groups’ - vision problems and deterioration of eyesight must be evaluated, and incorporated in designing and expanding existing and upcoming eye care initiatives.

While a focus on cataract operations needs to be sustained, the management and treatment of other eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and childhood blindness is also important. The control of such avoidable or treatable issues calls for periodic screening and monitoring for early detection and timely prevention.

Public health experts and community ophthalmology practitioners must consider targeting women and the elderly for efforts to curb blindness and evaluate local barriers to availing services, especially in rural and remote areas. Further, the socio-economic barriers that prevent women from seeking eye care, and the bottlenecks that hamper accessibility in rural areas, must be comprehensively explored and appropriately acted upon, for inclusive and universal eye care.

Integration of technology and an active and mindful push to research and innovation in the eye care sector, along with affordable spectacles, ophthalmic equipment, and specialised manpower, must be prioritised. Regional Institutes of Ophthalmology (RIOs), specialised institutions, civil society organisations, and the private sector, among others, must be strengthened through investment and capacity building to enable these.

The Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is essential to ensure access to the health services by patient including when and where it is needed, without financial hardship. UHC is a global priority for the WHO, and critical component for health-related Sustainable Development Goals. To achieve UHC, the people-centred approach to health services is key factor. This means putting the comprehensive needs of people and communities, not only diseases, at the centre of health systems, and empowering people to have a more active role in their own health.

Several notable eye care centres, through their facilities and treatment initiatives, provide a model for learning and propagation of best practices. One such centre, L.V Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI) in Hyderabad, provides affordable or free eye care of a high quality, bringing marginalised populations into the healthcare system, through its holistic ‘Pyramid of Eye Care’. This Pyramid, adopted by the Government of India as a model for eye care service delivery, rests on “creation of sustainable permanent facilities within communities, staffed and managed by locally trained human resources, and linked effectively with successively higher levels of care”.

Government figures reflect a reduction in prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in the country over the years, however, it is also seen that data, such as that from the VLEG/GBD 2020 Model, presents the current prevalence to be multiple times of the official figures. This requires further assessment, and also raises a concern about the non-availability of centralised data on interventions in the eye care sector from non-government and private players. This must be integrated with existing data, through regular, periodic, dynamic and real-time data and surveys with a wider scope, that include newer dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic, among others.

The eye care industry as a whole – not only public programmes – needs attention, towards developing an approach to universal eye health that champions planned investment and technology, providing targeted and quality services that are accessible and affordable.

Over the years, India has seen a great push to and improvement in the provision of eye care to its citizens, which is evident from the achievement of programmes such as NPCBVI. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly disrupted this progress over the past two years. The government has revised programme targets and set out to clear the backlog of cataract surgeries with a plan for the next three years. This renewed focus on universal and timely eye care intervention must be taken forward as a priority, and implementation remains the crucial challenge.

Availability, accessibility, and affordability must be at the centre of efforts in ensuring universal eye health. Existing eye care programmes must be strengthened and expanded, and infrastructure and ophthalmic equipment be maintained and upgraded. A key strategy to augment eye health that advances the attainment of the SDGs is to invest in eye care infrastructure and programmes, human resource development, in particular the development of ophthalmic personnel, and training for the integration of primary eye care into primary health care.

In a recent study by Seva Foundation and six leading eye health providers of the country, the costs of MSVI and blindness in India alone in 2019 are estimated at $54.4 billion at purchasing power parity exchange rates (range: $44.5-67.0 billion).

As the country’s population grows and ages, the burden of vision impairment and blindness will continue to increase, if mechanisms for timely and effective intervention are not maintained and strengthened. With India at 75, and moving towards India@2047, the importance accorded to eye care and eye health will be crucial in the coming years. Policy must move forward with a view to maintain India’s eye care ecosystem as a strength and asset, towards shaping the growth, wellbeing and self-reliance of the country and its ageing population in the years to come.

---

Arjun Kumar, Anshula Mehta and Simi Mehta are with IMPRI Impact and Policy Research Institute, New Delhi, and Kuldeep Singh is Regional Director, India and Bangladesh, Seva Foundation, USA. This article is an outcome of a research project supported by Seva Foundation, USA. Acknowledgements are due to various experts in the eye care sector and to the research team

Vision loss and impairment impacts more than how people see – their capability, employability, income, access to education and healthcare, and more. Vision makes an important contribution to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and with 80% of vision loss being avoidable (as per the WHO), there is a need for government to invest more proactively towards ensuring universal eye health. The National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCBVI) has played an important steering role in India’s efforts in blindness prevention in the South Asia region. Despite of majority of the causes of vision impairment are preventable or addressable through timely detection and screening, yet eye care is not an integral part of universal health coverage. The early advantage due to NPCBVI has now diminished and country is struggling to complete the cataract surgery backlog. However, at the same time, the high prevalence of refractive error is a huge concern for the country. With the last two years spent in the throes of the COVID-19 pandemic, many new issues for eye care have emerged, including the impact on availability and accessibility of eye care services, and children’s eye health in light of the online teaching-learning paradigm. The eye care sector needs a renewed thrust to clear the backlog of pending eye health services, including cataract surgeries, and to be well-integrated with the agenda of universal health care. Inclusion in coverage must remain a priority, as the country moves ahead with an ageing demographic towards the attainment of SDGs and India@2047.

Vision makes an important contribution to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and has been aligned with the attainment of each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) listed by the United Nations (UN). The inherent rationale behind this is that without proper vision and eyesight, the people remain at a lack in contributing their bit towards the 2030 Agenda. While attainment of Goal 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing) is inexorably linked to eye health, other major goals that are directly or indirectly impacted by the nature of eye health of the people include: 1 (No poverty); 2 (Zero hunger); 4 (Quality education); 5 (Gender equality); 8 (Decent work and economic growth), and 10 (Reducing inequality) and 9 and 11 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure, and sustainable cities).

Overall, the fact that SDGs are inherently advanced if the eye-health of the population is ensured. The United Nation’s Resolution in 2021 sets a target for eye care for all by 2030 – with countries set to ensure full access to eye care services for their populations, and, to support global efforts, to make eye care part of their nation’s journey to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The world Health Assembly’s resolution urges countries to “make eye care an integral part of universal health coverage; and implement integrated people-centered eye care, where people and communities are at the center within health systems”. Further 2021 Resolution aims to address cataract and refractive error, as the two major causes of vision impairment and blindness.

The WHO in its 2021 Factsheet on Blindness and Visual Impairment suggests that approximately 2.2 billion people across the world suffer from vision impairment or blindness. Of these, at least a billion people have a vision impairment that could have been prevented or is yet to be addressed. According to their evaluations, 90% of vision loss is concentrated in low- and middle-income countries, with the poor and vulnerable segments being disproportionately impacted in availability, access, affordability and quality.

India has been a frontrunner in ensuring eye care for its population, by instituting programmes like the National Programme for Control of Blindness (NPCB) (1976) which was renamed to ‘The National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCBVI) (2017), under the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), and subsequently has made remarkable progress in initials decades on implementation. The Trachoma Control Programme started in 1963 was merged under NPCB in 1976. However, owing to the challenges in catering to a large population, and evident gaps, a renewed thrust towards comprehensive and universal eye care is required.

This article discusses the eyecare statistics, policies and programmes, and assesses the progress of NPCBVI over recent years. It also highlights the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the issues concerning the programme and suggests the way forward towards universal eye health.

According to the Population Census of 2011, 2.2% of the population had disabilities, and the percentage of persons with Disability In Seeing (excluding those with multiple disabilities) was 0.4%.

The Survey of Persons with Disabilities in India conducted under the 76th Round (July – September 2018) of the National Sample Survey also reported a 2.2% prevalence of disability in the population, similar to the 2011 Census. The percentage of persons with Visual Disability (with or without any other disability) stood at 0.2% according to this Survey.

The Rapid Survey on Avoidable Blindness and the National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey, conducted under the National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCBVI) report the prevalence of blindness over several years.

It is important to note that over time there has been improvement. The National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey India 2015-19 indicates a 0.36% prevalence of blindness and 2.55% prevalence of visual impairment in the country. This survey uses better techniques and indicators at par with global standards, incorporating more inclusionary criteria. Key findings from the Survey suggest that cataracts are the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment among the population aged 50 years or over, accounting for blindness in 2 out of 3 persons and vision impairment in 7 out of 10 persons in this segment.

The Survey also puts forth that:

“The WHO Global Action Plan for Universal Eye Health 2014-2019 targets a reduction in the prevalence of visual impairment by 25% by 2019 from the baseline level of 2010. The WHO estimated a prevalence of blindness, MSVI and VI as 0.68%, 4.62% and 5.30% respectively in India for the year 2010. The current survey shows a reduction of 47.1% in blindness, 52.6% in MSVI and 51.9% in VI compared to the baseline levels. This shows that the target of 25% reduction in visual impairment have been achieved successfully by India.”

However, it is important to note that the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB), on the basis of the VLEG/GBD (Vision Loss Expert Group/Global Burden of Disease study) 2020 Model, reports that in 2020 in India, there were an estimated 270 million people with vision loss, of which, 9.2 million people were blind. Notwithstanding the recent national figures, these estimates by IAPB are multiple times, which raises and requires further scrutiny.

Background

Our eyes are the locus of primary access to the world around us. They allow us to interact with it and facilitate physical, emotional, and mental well-being. Vision loss and impairment affects more than how people see; it has implications for inequities in employment, healthcare access, and income. According to the World Health Organization (WHO), it has been estimated that 80% of vision loss is preventable or treatable. Yet, many populations do not have access to good-quality, affordable eye care. Thus, there is a need for every government to invest more proactively towards ensuring eye health security of the entire population.Vision makes an important contribution to the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and has been aligned with the attainment of each of the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) listed by the United Nations (UN). The inherent rationale behind this is that without proper vision and eyesight, the people remain at a lack in contributing their bit towards the 2030 Agenda. While attainment of Goal 3 (Good Health and Wellbeing) is inexorably linked to eye health, other major goals that are directly or indirectly impacted by the nature of eye health of the people include: 1 (No poverty); 2 (Zero hunger); 4 (Quality education); 5 (Gender equality); 8 (Decent work and economic growth), and 10 (Reducing inequality) and 9 and 11 (industry, innovation, and infrastructure, and sustainable cities).

Overall, the fact that SDGs are inherently advanced if the eye-health of the population is ensured. The United Nation’s Resolution in 2021 sets a target for eye care for all by 2030 – with countries set to ensure full access to eye care services for their populations, and, to support global efforts, to make eye care part of their nation’s journey to achieving the Sustainable Development Goals. The world Health Assembly’s resolution urges countries to “make eye care an integral part of universal health coverage; and implement integrated people-centered eye care, where people and communities are at the center within health systems”. Further 2021 Resolution aims to address cataract and refractive error, as the two major causes of vision impairment and blindness.

The WHO in its 2021 Factsheet on Blindness and Visual Impairment suggests that approximately 2.2 billion people across the world suffer from vision impairment or blindness. Of these, at least a billion people have a vision impairment that could have been prevented or is yet to be addressed. According to their evaluations, 90% of vision loss is concentrated in low- and middle-income countries, with the poor and vulnerable segments being disproportionately impacted in availability, access, affordability and quality.

India has been a frontrunner in ensuring eye care for its population, by instituting programmes like the National Programme for Control of Blindness (NPCB) (1976) which was renamed to ‘The National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCBVI) (2017), under the Directorate General of Health Services (DGHS), Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (MoHFW), and subsequently has made remarkable progress in initials decades on implementation. The Trachoma Control Programme started in 1963 was merged under NPCB in 1976. However, owing to the challenges in catering to a large population, and evident gaps, a renewed thrust towards comprehensive and universal eye care is required.

This article discusses the eyecare statistics, policies and programmes, and assesses the progress of NPCBVI over recent years. It also highlights the disruption caused by the COVID-19 pandemic and the issues concerning the programme and suggests the way forward towards universal eye health.

Eyecare Statistics

Several official sources report the prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in the country, based on varied approaches and definitions. While the Census and the National Sample Survey collect and report data on visual impairment and blindness under the ambit of disability, the Rapid Survey on Avoidable Blindness, and the National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey, conducted by the Dr Rajendra Prasad Centre for Ophthalmic Sciences, AIIMS, New Delhi, under NPCBVI, focus on the prevalence and causes of blindness and visual impairment in the country.According to the Population Census of 2011, 2.2% of the population had disabilities, and the percentage of persons with Disability In Seeing (excluding those with multiple disabilities) was 0.4%.

The Survey of Persons with Disabilities in India conducted under the 76th Round (July – September 2018) of the National Sample Survey also reported a 2.2% prevalence of disability in the population, similar to the 2011 Census. The percentage of persons with Visual Disability (with or without any other disability) stood at 0.2% according to this Survey.

The Rapid Survey on Avoidable Blindness and the National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey, conducted under the National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCBVI) report the prevalence of blindness over several years.

It is important to note that over time there has been improvement. The National Blindness and Visual Impairment Survey India 2015-19 indicates a 0.36% prevalence of blindness and 2.55% prevalence of visual impairment in the country. This survey uses better techniques and indicators at par with global standards, incorporating more inclusionary criteria. Key findings from the Survey suggest that cataracts are the leading cause of blindness and visual impairment among the population aged 50 years or over, accounting for blindness in 2 out of 3 persons and vision impairment in 7 out of 10 persons in this segment.

The Survey also puts forth that:

“The WHO Global Action Plan for Universal Eye Health 2014-2019 targets a reduction in the prevalence of visual impairment by 25% by 2019 from the baseline level of 2010. The WHO estimated a prevalence of blindness, MSVI and VI as 0.68%, 4.62% and 5.30% respectively in India for the year 2010. The current survey shows a reduction of 47.1% in blindness, 52.6% in MSVI and 51.9% in VI compared to the baseline levels. This shows that the target of 25% reduction in visual impairment have been achieved successfully by India.”

However, it is important to note that the International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness (IAPB), on the basis of the VLEG/GBD (Vision Loss Expert Group/Global Burden of Disease study) 2020 Model, reports that in 2020 in India, there were an estimated 270 million people with vision loss, of which, 9.2 million people were blind. Notwithstanding the recent national figures, these estimates by IAPB are multiple times, which raises and requires further scrutiny.

National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCBVI): Progress and Issues

The National Programme for Control of Blindness (NPCB) was launched as a 100% Centrally Sponsored scheme in 1976, but now from 12th Five Year Plan of India (2012-17), it is 60:40 contribution of central and state governments in all States/UTs and 90:10 in hilly states and all north-eastern States). The aim of the program is to reduce the prevalence of blindness from 1.4% to 0.3 % (by 2020). It was later renamed as National Programme for Control of Blindness and Visual Impairment (NPCBVI) in 2017. According to the 2021-22 Annual Report of MoHFW, the programme currently provides primary and secondary eye care services within the National Health Mission (NHM) framework with 60:40 cost-sharing between Centre and State (90:10 in North-Eastern States and other hilly States). Under the National Health Policy (NHP), the target is to reduce the prevalence of blindness to 0.25% by 2025. The programme activities are carried out under the National Health Mission (NHM) component and the Tertiary Eye Care component. The MoHFW fixed a target of 330 lakh cataract surgeries with an annual target of 66 lakh cataract surgeries under NPCB during the 12th Five Year Plan (2012-2017).As per the Pattern of Assistance under NPCBVI for 2017-20, outlined by MoHFW in 2018, the programme is part of the Non-Communicable Diseases (NCD) Flexible Pool under the NHM. Funds for implementation of the programme are released by NHM as grant-in-aid into the NPCBVI account, through the respective State Health Societies. The major activities for which grants-in-aid are provided are cataract operations, treatment/management of other eye diseases, distribution of free spectacles to school children (to District Health Societies (DHSs), eye banks and eye donation centres, training of paramedical ophthalmic assistants (PMOAs) and other paramedics, maintenance of ophthalmic equipment, district and sub-district hospitals and vision centres, Information Education Communication (IEC), and contractual manpower, among others. NGOs and private practitioners are reimbursed for cataract operations, and assistance is provided for the Government sector. Apart from this, other eye care services are also covered under Ayushman Bharat and various state governments have also designed their schemes, e.g., Chokher Alo (West Bengal), Cataract-Blindness Free Gujarat, Kanti Velugu (Telangana) and Dr. YSR Kanti Velugu (Andhra Pradesh), among others.

The Quarterly Review of the Programme (September 2019) lists its objectives and highlights major issues as follows:

Objectives:

- Reduce the backlog of blindness through identification and treatment of the blind.

- Develop comprehensive eye-care facilities at each level, i.e., Primary Health Centres (PHCs), Community Health Centres (CHCs), District Hospitals, Medical Colleges and Regional Institutes of Ophthalmology.

- Develop human resources for providing Eye Care Services.

- Improve quality of service delivery.

- Secure participation of Voluntary Organizations/Private Practitioners in eye care services.

- Enhance community awareness on eye care.

Major Issues:

- Low utilization of allotted funds by most of the States except Chhattisgarh and Sikkim

- Poor physical performance by many states, such as Nagaland, Sikkim, Lakshadweep, Meghalaya, Jammu and Kashmir and Jharkhand.

- Delay in NGO payments (for performing cataract and treatment of other eye diseases) by District Programme Officers in spite of their uploading of data in the MIS of NPCBVI.

- Quality issue: Sporadic episodes of cluster endophthalmitis keep coming in spite of circulation of prescribed eye surgery guidelines.

- Poor nominations for training: Very few nominations of eye specialists are sent by States for refresher hands-on training. This results in inadequate skilled/trained eye surgeons in States.

- Many of the States do not have sanctioned posts of Ophthalmologists at district level.

Over time, the programme has maintained a phenomenal pace in achieving its targets for cataract operations. However, the target set at national level are far from actual need of the cataract operation needed. Further, with the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, the programme performance has seen a decline. In light the backlog of cataract surgeries and the government’s push to clear it, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India has notified a special campaign ‘Rashtriya Netra Jyoti Abhiyan’ in May 2022 (vide D.O.No.T.12020/10/2022-NCD-1/NPCB&VI dated 18th May 2022) with a proposed total of 270 lakh cataract surgeries to be carried out over the next three financial years (2022-23 to 2024-25), various media reports in recent times has also covered and carried out governments’ ambition and plans for the same. This aim to increase the cataract surgeries by 17% in FY22-23, 40% in FY 23-24 and 63% in FY 24-25 without any additional investment in surgical infrastructure, human resource, training or by providing direct budgetary incentive to state or districts under Rashtriya Netra Jyoti Abhiyan.

Similarly, other programme activities – provision of free spectacles to school children suffering from refractive errors, treatment and management of other eye diseases, collection of donated eyes, and training of eye surgeons – have been carried out at a rapid pace over the years, but have seen a dip amid the pandemic. The International Agency for the Prevention of Blindness estimates 265.8 million people in India with visual impairment, which is highest in the world. However, the existing efforts for refractive errors screening and providing spectacles are limited to a very small part of the total target group, including children in schools.

Further, a Parliamentary Standing Committee on Health and Family Welfare [One Hundred and Twenty-Sixth Report on Demands for Grants 2021-22 (Demand No. 44) of the Department of Health and Family Welfare] in March 2021 noted that there had been underutilisation of funds earmarked for the purposes of capacity building of personnel, which requires attention.

As highlighted in Table 13, a cursory look at the expenditure of the NPCBVI suggests the backlog and impact of COVID-19 on the financial aspects. The total expenditure for the FY 2018-19, 2019-20 and 2020-21 was ₹ 396.8, 331.6 and 227.4 crore respectively. Moreover, the approval of expenditure for FY 2021-22 was increased to a whopping ₹ 724 crore, nonetheless, owing to the second and third wave of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2021-22, the utilisation has been a mere ₹ 140.5 crore, or around one-fifth of the approved expenditure. There are also statewise variations in the achievement levels as elucidated in Table 13. Thus, there is an urgent need to reinvigorate NPCBVI and the eye care sector by the Central and State Governments, having unmet target demands and unspent funds.

Issues in the Eyecare Sector and COVID-led Exacerbation

As efforts and targets in the eye care sector are expanded, quality remains a challenge while striving for quantity. This extends to the quality of cataract surgery, visual outcomes, surgical and ophthalmic equipment, spectacles, infrastructure, training of surgeons and allied ophthalmic professionals (AOP), and the soft aspects such as adequate information dissemination among citizens and prospective patients, in a targeted and sensitised manner.Accessibility continues to be a roadblock in moving towards universal eye care. Primary health care needs to be strengthened through an extensive health workforce, setting up of more PHCs and Vision Centres (VCs) and the provision of teleophthalmology, Multipurpose District Mobile Ophthalmic Units in District Hospitals, and the added participation of private and other voluntary players, among others.

It is important to add that NPCBVI, too, seeks to secure participation of voluntary and private organisations to expand the provision of eye care services. However, concerns regarding administrative and logistical glitches, and delays in payments to these organisations remain a roadblock in strengthening the reach and achievement of the programme.

Newer and diverse challenges have emerged in the recent years. The available data on vision loss and eye care is, for the major part, programme related. There is a dearth of overall data on the eye care sector, especially from the private and NGO sector to arrive at a complete picture. While data on eye care and metrics on programme achievements are available from various official sources, there is a need for centralised real-time availability of eye care statistics from all sources. A component of this challenge also lies in the quality of eye care data supplied at the primary level by states. Moving ahead, initiatives such as Digital India and Ayushman Bharat Digital Mission must take the lead in integrating health records on a real-time basis.

The COVID-19 pandemic poses challenges for reaching the population and implementation of initiatives. Digitalization of eye care services – via IEC messages and delivery of preliminary diagnoses via teleopthalmology in areas with difficult terrain, in part, may assist efforts towards awareness and coverage. The Medical Council of India has come up with a ‘Telemedicine Practice Guidelines for Enabling Registered Medical Practitioners to Provide Healthcare Using Telemedicine’ in 2020, which is a welcome step to address the access and human resources challenge. However, deployment of tele-opthalmology is critically dependent on technology, hardware infrastructure and connectivity to ensure the patent and registered medical provider’s Identification, mode of Communication, Consent of patient, consultation process, patient Evaluation and Patient Management process post evaluation and follow-up.

Prioritizing children’s eye health, in light of the pandemic-induced online teaching-learning process, is of utmost importance. Existing initiatives of school eye screenings and provision of free spectacles to children with refractive errors must be rigorously continued, and coverage expanded as per the evolving pandemic situation. COVID- and lockdown-induced emerging dimensions to children’s – as well as other age groups’ - vision problems and deterioration of eyesight must be evaluated, and incorporated in designing and expanding existing and upcoming eye care initiatives.

While a focus on cataract operations needs to be sustained, the management and treatment of other eye diseases such as diabetic retinopathy, glaucoma, and childhood blindness is also important. The control of such avoidable or treatable issues calls for periodic screening and monitoring for early detection and timely prevention.

Public health experts and community ophthalmology practitioners must consider targeting women and the elderly for efforts to curb blindness and evaluate local barriers to availing services, especially in rural and remote areas. Further, the socio-economic barriers that prevent women from seeking eye care, and the bottlenecks that hamper accessibility in rural areas, must be comprehensively explored and appropriately acted upon, for inclusive and universal eye care.

Integration of technology and an active and mindful push to research and innovation in the eye care sector, along with affordable spectacles, ophthalmic equipment, and specialised manpower, must be prioritised. Regional Institutes of Ophthalmology (RIOs), specialised institutions, civil society organisations, and the private sector, among others, must be strengthened through investment and capacity building to enable these.

The Universal Health Coverage (UHC) is essential to ensure access to the health services by patient including when and where it is needed, without financial hardship. UHC is a global priority for the WHO, and critical component for health-related Sustainable Development Goals. To achieve UHC, the people-centred approach to health services is key factor. This means putting the comprehensive needs of people and communities, not only diseases, at the centre of health systems, and empowering people to have a more active role in their own health.

Several notable eye care centres, through their facilities and treatment initiatives, provide a model for learning and propagation of best practices. One such centre, L.V Prasad Eye Institute (LVPEI) in Hyderabad, provides affordable or free eye care of a high quality, bringing marginalised populations into the healthcare system, through its holistic ‘Pyramid of Eye Care’. This Pyramid, adopted by the Government of India as a model for eye care service delivery, rests on “creation of sustainable permanent facilities within communities, staffed and managed by locally trained human resources, and linked effectively with successively higher levels of care”.

Government figures reflect a reduction in prevalence of blindness and visual impairment in the country over the years, however, it is also seen that data, such as that from the VLEG/GBD 2020 Model, presents the current prevalence to be multiple times of the official figures. This requires further assessment, and also raises a concern about the non-availability of centralised data on interventions in the eye care sector from non-government and private players. This must be integrated with existing data, through regular, periodic, dynamic and real-time data and surveys with a wider scope, that include newer dimensions of the COVID-19 pandemic, among others.

The eye care industry as a whole – not only public programmes – needs attention, towards developing an approach to universal eye health that champions planned investment and technology, providing targeted and quality services that are accessible and affordable.

The Way Forward towards Universal Eyecare and Attainment of SDGs

Given the intricate relationship of eye health and the growth and well-being of the populace, the issue must become a priority for policymakers, academics, civil societies and NGOs, and the private sector.Over the years, India has seen a great push to and improvement in the provision of eye care to its citizens, which is evident from the achievement of programmes such as NPCBVI. However, the COVID-19 pandemic has undoubtedly disrupted this progress over the past two years. The government has revised programme targets and set out to clear the backlog of cataract surgeries with a plan for the next three years. This renewed focus on universal and timely eye care intervention must be taken forward as a priority, and implementation remains the crucial challenge.

Availability, accessibility, and affordability must be at the centre of efforts in ensuring universal eye health. Existing eye care programmes must be strengthened and expanded, and infrastructure and ophthalmic equipment be maintained and upgraded. A key strategy to augment eye health that advances the attainment of the SDGs is to invest in eye care infrastructure and programmes, human resource development, in particular the development of ophthalmic personnel, and training for the integration of primary eye care into primary health care.

In a recent study by Seva Foundation and six leading eye health providers of the country, the costs of MSVI and blindness in India alone in 2019 are estimated at $54.4 billion at purchasing power parity exchange rates (range: $44.5-67.0 billion).

As the country’s population grows and ages, the burden of vision impairment and blindness will continue to increase, if mechanisms for timely and effective intervention are not maintained and strengthened. With India at 75, and moving towards India@2047, the importance accorded to eye care and eye health will be crucial in the coming years. Policy must move forward with a view to maintain India’s eye care ecosystem as a strength and asset, towards shaping the growth, wellbeing and self-reliance of the country and its ageing population in the years to come.

---

Arjun Kumar, Anshula Mehta and Simi Mehta are with IMPRI Impact and Policy Research Institute, New Delhi, and Kuldeep Singh is Regional Director, India and Bangladesh, Seva Foundation, USA. This article is an outcome of a research project supported by Seva Foundation, USA. Acknowledgements are due to various experts in the eye care sector and to the research team

Comments