By Manish Priyadarshi, Simi Mehta, Balwant Singh Mehta, S Jayaprakash, Dolly Pal, Bharathy, Navneet Manchanda, Ritika Gupta, Anshula Mehta, Arjun Kumar*

Human health is a prerequisite for the economic health of any country. Unless the population is healthy, the economy of any nation cannot perform. This hypothesis has been validated by the outbreak of the novel coronavirus disease (COVID-19), due to which the world has been hit by pandemic and daunting economic recession. In this light, the mother and child health (MCH) cannot be underrated as pregnant women, infants and small children are more susceptible to infections and many other causes of illness than others.

Maternal health is related to care of women’s health at the time of pregnancy, pre-natal, intra-partum, childbirth and the post-partum period. Literature is replete with evidence that shows the entire phase of motherhood to be socially, economically and psychologically vulnerable. Understandably, this article argues not just for strengthening maternal healthcare but also the need to improve the various aspects of living conditions that promote health and hygiene. For instance, while the institutional deliveries have increased in the country, as evidenced by various National Family Health Surveys (NFHS) — from 39% in 2005-06 to 79% in 2015-16 to 94.3% in 2018-19, the prevailing pandemic and the ensuing lockdown has posed several legitimate concerns and challenges for expectant mothers and parents having children up to the age of 5 years. The basis of all this is the closure of doctors’ clinics, outpatient departments (OPDs) of hospitals and the Anganwadi centres (AWCs) providing various types of health care advice to the patients.

Given this background, this article seeks to fathom the extent of the reach of current MCH services in India, the ways in which the pandemic has affected such services and the possible way forward in ensuring and assuring healthcare benefits to mothers, children of the age group 0-5 years in India amid COVID-19 and prevailing lockdown fallouts.

Insights on MCH in India: Evidencing Official Statistics

A study on The Incidence of Abortion and Unintended Pregnancy in India, 2015 estimated an annual 48.1 million (4.81 crore) pregnancies with 15.6 million abortions in India, in 2015. Women of reproductive age (15- 49 years) constitute 56% (36.8 crore) of the total female (65.4 crore, which is 48.7 % of total population of 134.3 crore) and 27% of total population of the country. In rural areas, it is 67% and in urban areas, it is 33% of the total female population. Children of 0-5 years comprise 10% (12.6 crore) of the total population, with 71% in rural areas and 29% in urban areas. Therefore, in totality, the purview of MCH consists of at least 37% or around 50 crore of the total population.Important indicators of MCH are the status of maternal and infant/child mortality rate. At present, India remains far from achieving desired outcome, but has had major progress in reducing maternal and infant/child mortality and improving the health of these constituents of its population. In fact, the World Health Organization (WHO) lauded India’s effort in reduction of maternal mortality, infant mortality, neo-natal and post-natal mortality, which are on track towards the achievement of Sustainable Development Goal-5. This is evident from the following statistics:

Maternal Mortality Rate (per one hundred thousand live births): The MMR has declined steadily from 178 per one hundred thousand live births in 2010-12 to 122 per one hundred thousand live births in 2015-17 (Figure 1). One of the main reasons for the decline in MMR is the rise in institutional deliveries in public facilities, which almost tripled, from 18% in 2005 to 52% in 2016. With the inclusion of private health facilities, institutional deliveries stand at 79%.

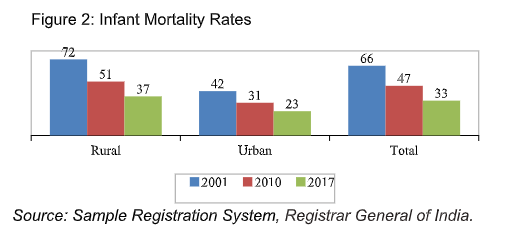

Infant Mortality Rate (per one thousand live births): The infant mortality rate has declined by almost half from 66 per 1000 live births in 2001 to 33 per 1000 live births in 2017 (Figure 2). Over the years, the gap in under-five mortality rates between urban and rural areas has reduced between 2001 and 2017, but remains significant.

Neo-Natal Mortality Rate (per one thousand live births): The neo-natal mortality rate has reduced from 40 per 1000 live births in 2001 to 24 per 1000 live births in 2017 (Figure 3). But there is a significant difference between rural and urban areas, i.e. 27 and 14 per 1000 live births in 2016.

Post-Natal Mortality Rate (per one thousand live births): Similarly, the post-natal mortality rate has also declined more than half from 26 per 1000 live births in 2001 to 11 per 1000 live births in 2016 (Figure 4). Over the years, the gap in neo-natal mortality rates between urban and rural areas has reduced from 11 points to just 2 points during the 15-year period.

Other MCH Indicators: According to the Indian government maternal health guidelines, every pregnant woman must mandatorily avail 3 or more antenatal care visits along with 90 or more Iron Folic Acid tablets and 2 or more Tetanus toxoid (TT) injections. The latest National Family Health Survey-4 (2015-16) gives important insights on MCH:

Maternity care such as mothers who had antenatal check-up in the first trimester (59%), mothers who had at least 4 antenatal care visits (51%). Mothers who consumed iron folic acid for 100 days or more when they were pregnant (30%), and mothers who received postnatal care from a doctor/nurse/lady health visitor (LHV)/ ancillary nurse midwife (ANM)/midwife/other health personal with 2 days of delivery (63%) has gone up almost twice in last one decade.

In addition, the delivery care like institutional birth (79%) including institutional births at public facility (52%) and home delivery conducted by skilled health personal out of total deliveries (4.3%) has also increased manifold during the last one and half decade period. In the case of children aged 12-23 months, over 62% were fully immunized (BCG, measles, and 3 doses of polio and DPT) in 2015-16. These figures indicating increasing access to mothers to public health care facilities and health personnel over the years.

Government Role in Providing MCH Services

MCH services include the needs during the process of childbearing as well as routine new-born care, the antenatal screening, nutrition for mother and psycho-social support. India has institutionalized an impressive infrastructure for delivering MCH services through a network of sub- centres, primary health centres (PHC), community health centres (CHC), district hospitals, state medical college hospitals, and other hospitals in the public and private sectors. The maternal health programme is a home-based programme implemented by auxiliary nurse midwives (ANM) and accredited social health activist (ASHA) with forward linkages with PHC, CHC and District hospitals (DH) if it’s a high risk or complicated pregnancy. In rural India, ASHAs work closely with Anganwadi workers (AWWs), frontline workers (FLWs) from the Integrated Child Development Services (ICDS). These are linked with HMIS, a digital initiative, and the progress are reported and monitored in real time. ASHAs and AWWs organize monthly health, sanitation, and nutrition days of the communities with institutional support from ANMs from the nearest health centres. A Cochrane Review demonstrated that community-based interventional care packages, delivered by a range of community‐based workers are effective in significantly reducing maternal and neonatal morbidity and mortality.The Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY) was launched in 2005 to reduce maternal and infant mortality by promoting institutional delivery among pregnant women. Under the JSY, eligible BPL/SC/ST pregnant women are entitled to cash assistance irrespective of the age of mother and number of children for giving birth in a government or accredited private health facility. The scheme also provides performance- based incentives to ASHA workers for promoting institutional delivery among pregnant women. The Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakram (JSSK) was launched in 2011 with the objective to eliminate out of pocket (OOP) expenses for both pregnant women and sick infants (till one year after birth) accessing public health institution for treatment.

Mission Indradhanush, launched in 2014, aims to ultimately achieve full immunization coverage for pregnant women and children. During the various phases of Mission Indradhanush including Gram Swaraj Abihayan and Extended Gram Swaraj, and two rounds of Intensified Mission Indradhanush 2.0, a total of 3.61 crore children and 91.45 lakh pregnant women have been vaccinated.

Government of India also launched the Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY) in 2017. It is a direct beneficiary transfer scheme for maternity benefit for providing cash incentive in three insta lments according to various stages of pregnancy and completion of vaccinations for the new-born. Under PMMVY, 1.2 crore beneficiaries have received benefits amounting to Rs. 4938 crore in 2019-20, although 1.37 crore applicants are registered under the same scheme. Comparatively, maternity benefits amounting to Rs. 2598 crore were released to approximately 70.6 lakh beneficiaries in 2018-19.

Launched in 2018, the Prime Minister’s Overarching Scheme for Holistic Nutrition or the POSHAN Abhiyaan or National Nutrition Mission focuses on improving nutritional outcomes for children, adolescent girls, pregnant women and lactating mothers in a time-bound manner during its three years. While it does not have a provision for providing nutritious food, the Take-Home Rations (THR) scheme under ICDS’ Supplementary Nutrition Program (SNP) targets exactly this. However, according to a survey conducted by the NITI Aayog in 27 aspirational districts of the country, only 46% pregnant and lactating women received THR, despite an enrolment rate of 78%. As a whole, the SNP had 71.8 lakh pregnant and lactating women as beneficiaries for 2018-19, and as on 30.09.2019 had 8 crore total (pregnant and lactating women + children between the ages of 6 months and 6 years) beneficiaries of which roughly 1.5 crore were pregnant and lactating women.

A program like JSSK was introduced in 2019 called the SUMAN scheme or Pradhan Mantri Surakshit Matritva Abhiyan (PMSMA), under which pregnant women, mothers up to 6 months after delivery, and all sick newborns will be able to avail free healthcare benefits.

At present, these myriad schemes are reaching out to around 1/4 to 1/3 of the estimated pregnant mothers. As more and more individuals emerge in need due to the fallback in livelihood stemming from the nationwide lockdown, it is necessary to take these schemes further by increasing the scope of coverage. At least two-thirds of the target population of pregnant women should be reached out to in a structured and timely manner, with the focus shifting from peripheral Aadhaar linkages to concrete action. The budget allocation for schemes pertaining to MCH should be re-prioritized and adequately increased – ideally doubled – for this proposed increase in coverage for the current year.

A centrally funded COVID-19 Emergency Response and Health System Preparedness Package worth ₹ 15,000 crores was approved on April 9, 2020. It will be implemented in three phases – from January 2020 to June 2020, from July 2020 to March 2021 and from April 2021 to March 2024. This fund will be divided among all states and union territories. Keeping the gravity of the challenges faced specifically in the provision of MCH in the times of the COVID-19 pandemic, this package should focus on incorporating accessible infrastructure for safe deliveries.

While the government initiatives are commendable and have gone a long way in reducing the MMR and IMR and the efforts are also appreciated by WHO, yet the Sustainable Development Goal 3 of reducing the MMR to less than 70 per 100,000 live births and to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and infant mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births seems a distant goal. In fact, the Jaccha-Baccha Survey (JABS) conducted across 6 states of India in 2019 demonstrated that less than half of pregnant women in rural India eat nutritious food and majority are deprived of quality healthcare. While the reasons for these can be deliberated separately, what becomes important is the enormity of issues that can and have already begun to overlap because of the outbreak of COVID-19.

COVID-19 and MCH Services: The Way Forward

Due to nationwide lockdown currently in force, necessary providers of MCH services like the AWCs have been closed as per the government orders and rightly so. But the question that arises is the ways in which the beneficiaries would access the various services. Pregnant and lactating mothers and children in both rural and urban areas have begun to suffer. For instance, the government order to the AWWs to home-deliver the dry ration for children and mothers has had problems in execution. AWWs have complained about the distance to be travelled on foot because of lack of personal or public vehicles, villagers (especially men) threatening and in some cases even beating the women AWWs for coming out of their homes violating lockdown, and added financial burdens as they have not been paid to purchase the ration since last one year or provided with protective gears. Another challenge that has emerged is the inability of the ANMs and ASHA workers to come to the rescue of pregnant mothers and infants for their vaccination as well as to arrange transportation to the nearest health facility for delivery, especially adhering to the service level benchmarking to combat the pandemic.While it is not known what the future will be once the lockdown comes to an end, some of the immediate steps to be undertaken are discussed below:Harness the technology and the advantage of mobile phone and internet penetration to the remotest area of the country. For instance, geo-tagging of the beneficiary and provision of tele-medicines, using location data, call data, and HMIS database. In this situation, the health practitioner will only receive cases needing advice due to high-risk pregnancy like ante-partum haemorrhage (APH), gestational hypertension (PIH/GH), eclampsia and severe anaemia. To distinguish between severe and normal cases, the programme can be administered by machine learning and Artificial Intelligence (AI).

All recent beneficiaries of JSY and PMMVY having been assigned Unique IDs should be used for direct benefit transfers (DBT), provision of nutritional assessment, screening of COVID-19, delayed appointments until self-isolation, triage referrals and referral to secondary care hospitals.

As an emergency measure, pregnant women (especially migrant workers) travelling or in transit on at the time of COVID-19 and seeking institutional delivery can be imparted with the benefits of the Pradhan Mantri Jan Aarogya Yojana (PM-JAY) or Ayushman Bharat (AB) with the participation of private sector.

Creation of a MCH dashboard in line with Ayushman Bharat and PMMVY Dashboard to synchronize the data, harnessing HMIS and ICDS database and show the facility close to pregnant mother for the rapid welfare delivery and integration of immunization services for the home-based new born care so that all the essential immunization can be given to the children below 2 years of age without any delays.

The dashboard can also track the whereabouts of pregnant women (of the region/ district/ city/ state in focus) and put mobile phones reminders on their and the cell phones of their family members, which would provide regular information on the precautions they need to maintain and the ways to respond if they catch flu-like symptoms, etc. These can be integrated with the existing applications of the government and must be triaged after primary screening.

This advice may be hard to follow in pregnancy; most women have monthly to weekly interactions with the health system during pregnancy for prenatal check-ups but in the times of the pandemic this may go missing, so it is imperative to keep them informed via digital medium. For instance, the Kilkari application of the Haryana Government can be scaled up to include video messages for women, specific to their stage of pregnancy. Frequent live conversations with the doctors/health practitioners needs to be arranged to reduce the anxieties and negative psychological impacts due to the spread of COVID-19 and lockdown in effect.

WhatsApp account must be set up where pregnant and lactating women are able to share their concerns and through audio and video messages, and volunteers can be roped with support of civil society and community networks.

Coordinators of Self Help Groups in the villages must be identified who would assist the ASHA workers and ANMs in-home delivery of required medicines. While this would help in reducing the burden on the latter two, it would also help expand community cohesion. For this, the SHGs can be awarded certificates of appreciation that would add to the merit of a strengthening the credit scores for availing any further loans from the banks.

An urgent separate database for tracing and surveillance on the recently travelled and migrated pregnant women must be prepared and each of them must be frequently contacted to ensure if they have been infected with the coronavirus.

The government has identified both private and public hospitals that are ready for coronavirus infected patients in each district. The contact numbers of these hospitals should be publicized through every available medium, so that the people use these when they or their family members develop COVID-19 symptoms.

Pregnant women who become infected should be treated with WHO-recommended supportive therapies in consultation with their obstetrician/ gynaecologist. These therapies must be informed to the pregnant women and the health practitioners without any further delay.

It is also important to record all new cases of pregnancies among all segments (coronial baby boomers) due to COVID-19 lockdown, so that government prepares for impending coronial generation after 10 months, and also have a ready benchmark for future shutdowns based on the lessons learnt. The existing HMIS and ICDS database, howsoever not very reliable, yet can be low hanging fruit in this regard to utilise the Digital India architecture.

In the lockdown scenario, the government must ensure that the services of AWWs are notified as essential services if it does not want the health and nutrition security of the women and children to be compromised. All pending payments due to the AWWs be transferred to the bank accounts without any further delays. It must be noted that the Budget 2020-21 has allocated Rs. 28,600 crore for programmes that were specific to women. It is indeed a matter of concern that the reimbursement for the purchases made for preparing mid-day meals for children at AWCs has not been released for over seven months in states like Jharkhand. With the present budget outlay, there should be no financial excuse to withhold the payments due to the AWWs, and in fact, they must be paid a three-month advance honorarium to facilitate their work and ensure their safety.

Expanding health insurance coverage to women and children will increase their access to necessary health services more than other groups. Along with the maternal and child health programs, this must be added with the existing public health and community services such as prenatal care and well-child care, and enabling services such as case management, transportation, and home visiting.

The maternal healthcare services must include mental health care, contraceptive services and supplies; diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted diseases; prenatal, intrapartum, and postpartum care; regular breast and pelvic exams (including Pap tests), in accordance with well-recognized periodicity schedules; risk assessment; and adequate education and counselling to support these interventions. Participants also outlined children’s health care needs, which vary at different ages. For the children up to 0-5 years, emphasis must be on preventive services, such as immunizations, and the monitoring of physical and psychosocial growth and development, with attention to critical periods in which appropriate care is essential for sound development and progress.

A separate, more comprehensive midwifery training programme with service level benchmarking in India must be introduced on an urgent basis. Having well-trained and capable midwives would provide a better birthing experience for the mother and would reduce the burden on obstetricians.

Women’s Self-Help Groups (SHGs) should be roped in for better outcomes in ensuring the provision of THRs. There should also be certain modifications and expansion in the type of food provided, varying regionally, to meet nutritional requirements. Planning of resources is a must to avoid misallocation and panic.

Blueprint for an alternative makeshift hospital arrangement for safe delivery and safe abortion in each district/blocks/city

While shutting down of doctors’ clinics, OPDs of hospitals and the AWCs have raised enormous difficulties, this seems to be the only way forward to avoid pregnant women, new-born and infants from succumbing to the coronavirus disease. It is also true that while termination of pregnancy is an option in the initial weeks to ensure that mother and the fetus do not catch the disease, but for those mothers in advanced and high-risk stages of pregnancies, the COVID-19 challenge is severe. Added to this is the stigma attached to abortion and not all couples would prefer this. It could add to the physiological complications for women hindering further conceptions.According to the HMIS, India has 705 districts, which translates into an average of over 2000 deliveries per month (and lesser than 1000 abortions), per district. Lately, new-borns are being delivered in unsafe settings as was the case in a Mumbai hospital where a woman and her three-day old child tested positive for COVID-19 after being given a room previously occupied by a COVID-19 patient. In Rajasthan, a doctor denied treatment to a pregnant Muslim woman – and her new-born died.

With the coronavirus crisis expected to continue and peak in the next few months, it is imperative to urgently design and implement alternate solutions which ensure institutional deliveries, facilitate treatment to the pregnant mothers and their new-borns and address MCH in a timely and structured manner, simultaneously adhering to social distancing and isolation. Some of these are discussed below:

Formation of Task Force/ Coordination Committee: Recently, in a video conference, the Union Cabinet Secretary advised district collectors to devise district-level containment plans for COVID-19. As part of this plan, we recommend providing adequate alternative spaces (preferably centralised within a district or block) for the delivery of babies, since hospitals are already chocked and unsafe in such a time due to the inherent risk of infection. Every district is equipped with a circuit house or any such similar institutional buildings (university grounds, schools, governments stadiums, convention halls etc., currently not in use anyways), which can be used as alternative to the hospitals and medical centres affected by coronavirus. Make shift hospitals with logistics planning for physical infrastructure, machinery, equipment and tools such as masks, gloves, surgical tools and beds can be quickly developed with the support of local governments, private sectors, governments consultants, civil society, etc.; for this commitment of corporate social responsibility (CSR) and multi-lateral organisations should be tried for. Post-delivery care – such as providing nutrition to the mother and child and practising WASH hygiene – can be provided by the pregnant individual’s family and/or community. Empanelled vehicles are also being used in some States to provide transport to pregnant women and children e.g. Janani express in MP, Odisha, Mamta Vahan in Jharkhand, Nishchay Yan Prakalpa in West Bengal and Khushiyo ki Sawari in Uttarakhand. These, clubbed with civil society and CSR interventions, would cover the crucial component of transport and mobility.

This is only possible with full and unwavering support from district officials, and the joint action of local administration and the private sector. To realise this proposition, it is recommended to form a taskforce or a coordination committee in every states (and districts) which should consist of stakeholders from every segment of maternal and child health, viz., pregnant women, and members of their family or community (representing the beneficiary population), AWWs, eminent citizens (businesses, technocrats, individuals from civil society who have demonstrated commitment to the cause), doctors, secretary of Department of Women and Child Development and other relevant persons. These members can hold deliberations through virtual meetings. Private sector and NGOs should assist the district administration in implementing such interventions. This support could be in the form of manpower, funds, or other services, depending on the capabilities of the organisation.

The whole process is focused on non-cash and in-kind help from stakeholders across different facilities – building, transportation, nursing and equipment – to provide a safe environment and support for delivery and postnatal and postpartum care, with the spirit of volunteerism in this difficult time for urgent action.

Ayushman Bharat: Viable or not?: It can be proposed that Ayushman Bharat Yojana can cover the insurance cost of the pregnancy while going through private hospital deliveries. However, private hospitals may not necessarily sign up for this, as their past dues are still outstanding and they have incurred huge costs in the deliveries of the women.

Information Technology (IT) intervention and Research and Development (R&D): R&D needs the intervention of IT to make significant strides towards effective MCH in this crisis. Digital India emphasizes the need to digitize service delivery. Similarly the Smart City Mission should be complemented with the proposed IT-research enabled solutions to provide smart delivery of these services. Integrated dashboards, wherever developed, should be incorporated with other such measures to develop Uniform Control and Command Centres for COVID-19 – which would have an MCH component, using data on locations, communication and medical history and treatment. This could draw inspiration from the ICT-based PRAGATI (Pro-Active Governance and Timely Implementation) platform. The Civil Registration System faces challenges in terms of timelines, efficiency and uniformity, and is looking to introduce IT-enabled automation in its processes for drastic improvements and real-time functioning. In the area of MCH too, it would only be prudent to turn to a well-oiled HMIS for planning now, to maintain a trajectory of positive change.

Plight of AWWs, ASHAs and ANMs: AWWs, ASHAs and ANMs are at the frontlines of tackling this crisis head-on, with an increased risk of infection. As of 2019, there were close to 14 lakh AWWs and 13 lakh Anganwadi Helpers (AWHs) in the country. ASHAs are roughly 9 lakh in number. Their uncleared dues, should be processed and remunerations regularised on an immediate basis. They should be provided with advance payments of three to four months to facilitate their work, insurance and safety and/or direct transfers and other forms of assistance in the same way as MNREGA workers. Further, it is a ripe time to reward them with the Governments decided minimum wage and linkages social security schemes.

This will facilitate each case of pregnancy to be treated on a case-to-case basis and ‘non-COVID only’ hospitals/ consultation and diagnosis centres must be ensured and these along with the AWCs must be sanitized multiple times a day. This is because the various facets of maternal health are closely associated with maternity risks e.g. sanitation, hygiene, nutrition and traditional beliefs.

Summing up

To conclude, with the deferral of direct and indirect taxes and other such payments for the three months (which are the main sources of revenue for the government), the revenue generation has dried up and is expected to continue this year. In this scenario, it becomes further pertinent to re-prioritise and explore alternatives – requiring minimal financial intervention from the government – on an urgent basis for planned and adequate MCH services during the livelihood lockdown and pandemic. All relevant stakeholders, including responsible and committed citizens, would have to come forward to devise and fructify a solution especially for mother and child care, whose practical considerations would include an adherence to service level benchmarking to combat coronavirus pandemic.There have been reports of increased dilemma of transferring the virus to the new-born child from the mother and leads to an agonizing situation of separating them from the mothers and being put in isolation wards. Perhaps, it would be wise for couples to delay their pregnancy planning until the pandemic scare is over- to relieve themselves of dealing with a yet another stress of the virus in the child-bearing process.

---

*Corresponding author: Prof. Manish Priyadarshi (manish@iihmr.org), Associate Professor, Department of Public Health, Indian Institute of Health Management Research (IIHMR), New Delhi and a Visiting Fellow at Impact and Policy Research Institute (IMPRI), New Delhi. All other co-authors are with IMPRI, New Delhi

Comments