By Moin Qazi*

Sanitation is the key to proper hygiene and is extremely essential for a healthy population. Till a few years back, India’s record on basic sanitation was horrific. The 2011 Census found that more Indians have access to mobile phones than to toilets. It must be said to the credit of the Modi Government that after coming to power, it got down to addressing the most fundamental problems of the people like sanitation and e-financial inclusion instead of launching grandiose but abstract programmes.

Singapore was born as an independent state in 1965 but inherited vast poverty. Freedom meant little promise of a decent life. Lee Kuna Yew, the country’s founding father and the first Prime Minister, found that Indonesia’s public health system was in a pathetic state and there were frequent outbreaks of typhoid, cholera and other life-threatening diseases. Lee knew a sick nation couldn’t be productive but Singapore didn’t have the time or resource to build a robust health system for handling the huge disease burden. Renowned for his visionary acumen, Lee realised the power of hygiene and sanitation in health and focused on the well-being of citizens very early. He invested in healthcare and showed the world the huge dividends of this basic intervention.

Toilets are the world’s cheapest preventive medicine. In a poll by the British Medical Journal, sanitation was voted the greatest medical milestone of the last 150 years—higher than antibiotics, vaccines and anesthesia. It is the best way to improve immunity against health hazards. Lacking access to a toilet involves more than just embarrassment and inconvenience. It’s also a significant health hazard. The risks associated with open defecation are not just from the disease but we must also take into account the humiliation and shame undergone by those who squatter in a gutter or bush. Because India’s population is huge and densely settled, it is impossible to keep human faeces from wells, farming land and children’s hands.

Prime Minister Narendra Modi took Lee Kuna Yew’s path, as he knew it was the least travelled and launched Swachh Bharat Abhiyan or Clean India Mission to modernise sanitation within five years by setting a target of building 110 million toilets, the largest toilet building programme in the history of mankind. Since Lee’s revolutionary experiment, decent, non-sewered, affordable, on-site water-conserving, toilets have revolutionised sanitation systems. Innovators have improved basic latrine toilets by developing ‘off the grid’ locations with new waterless technology for treating waste to make it cleaner and to biodegrade or compost its content.

Some ‘dry’ models use sawdust for ash to douse the waste. By using dry toilets, not only do you save water, you can actually use the waste for fertilisation purposes. Models are constantly upgraded to make it relevant to time: Toilet pans are now manufactured from attractive plastic and cheaper and more durable accessories are reducing costs and enhancing life. Rural toilets are usually a hole in the ground with two planks. Farmers collect human waste for composting to fertilise crops. Flush toilets deprive them of composting material and septic tanks require extra cost and effort to empty and clean. We now have toilets that require no connections to water, sewer or electrical lines.

At present, toilets that are built are mostly single-pit latrines that need to be emptied at least once every few years. Where the pits are lined at the bottom, the seepage will need to be pumped out more regularly, but there will have to be measures to ensure that it is not disposed of in neighbouring fields or rivers.

Where the pits are not lined, groundwater quality can be affected. In Kerala, most houses have an unlined pit on one side of the house and a well-used for drinking water on the other side, thus posing health hazards. Since groundwater is the source of drinking water for around 80 per cent of the population in India, this aspect needs to be kept in mind. In India, emptying a latrine is a taboo in a way that it isn’t in other places. Instead of adopting an affordable technology, people either defecate in the open or use expensive technology that can be emptied with a vacuum where nobody has to interact with faeces. An important point here is that if people use the twin pit toilet (a system in which two pits are constructed so that when one fills up, it can be covered and allowed to sit for decomposition) in a way the Government and international organisations recommend, there will not be an issue of biological danger from faeces because they’re supposed to decompose in six months and can be emptied.

Lack of sanitation has obvious and glaring health hazards leading to cycles of contamination and infection that impose a heavy cost on human, economic and environmental health. Such societies also tend to have the highest number of child deaths. For instance, women have specific sanitation needs related to menstrual hygiene. Fortunately, Governments around the world are improving sanitation with innovative non-sewered solutions that are more flexible and affordable — often at one-seventh the cost of sewers. Investments in clean sanitation contribute positively to both economic and health outcomes, such as increased worker output, reduction in cases of chronic diarrhoea and children’s improved attendance and performance in schools.

UNICEF undertook a study across 10,000 rural households in 12 cities to estimate the cost benefits of the mission. It found out that every rupee invested in improving sanitation will help save Rs 4.30. The study found that the campaign could lead to each household saving around Rs 50,000 per year. The study concluded that if 85 per cent of household members use their washrooms to defecate, the financial savings induced by improved sanitation had a cost-benefit ratio of 430 per cent on average. In other words, one rupee invested allows a saving of Rs 4.30. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), every dollar invested in sanitation yields on an average, $5.50 in economic returns.

India could learn from other so-called Third World nations, including our neighbour Bangladesh, which reduced open defecation from 34 per cent in 1990 to just one per cent in 2015 without as much subsidy. As part of a sustained effort, its Government partnered with village councils to educate people on the overall merits of proper sanitation. Instead of just focusing on the hazards of open defecation, the Bangladeshi Government extolled the virtues of clean sanitation — with women playing a vital role in the success of the campaign. A toilet soon became a symbol of equality.

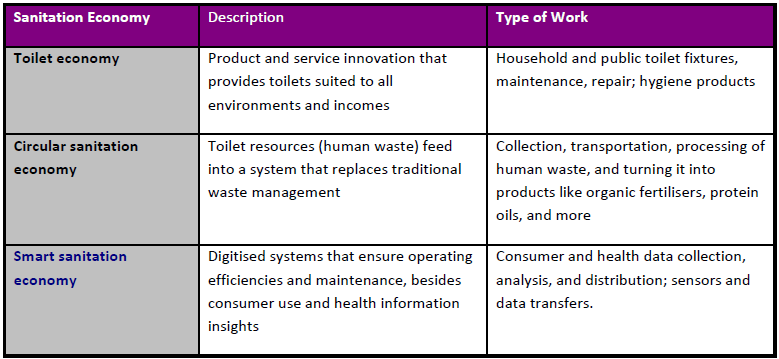

The three-year-old Toilet Board Coalition (TBC), a global consortium of companies, social investors, sanitation experts and non-profits, aims to catalyse market-based solutions to fulfill the UN’s Sustainable Development Goal of achieving adequate and equitable sanitation and hygiene for all and ending open defecation by 2030. With millions of new toilets, more sanitation workers will be needed to carry out faecal sludge management. This will be difficult as such jobs are stigmatised.

Here are the three sub-sectors of the sanitation economy as identified by Toilet Board Coalition (TBC):

The momentum built by the Government is certainly going to propel entrepreneurs to come up with creative solutions to eliminate some of the glitches. The ecosystem is fast taking shape and convergence among various stakeholders and actors should help us see an end to this uncivilised practice of open defecation.

—

*Development expert

Comments