By Rajiv Shah

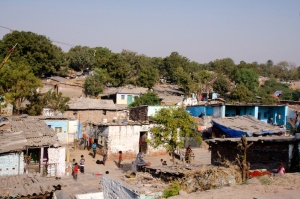

Even as the Gujarat government is planning to come up with a new slum policy 2013, with “rehabilitation” of the slum-dwellers with the help of private developers as the key thrust, available literature suggests that any effort to uproot slum dwellers would mean further heightening their already vulnerable status.

Recently, in a paper, “Low Carbon Green Growth Roadmap for Asia and the Pacific”, providing a roadmap for citywide slum upgradation, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) said that “the poor and the vulnerable in cities and towns can aspire to have security, shelter, basic infrastructure and services with citywide slum upgrading”, adding, “Up to 35 per cent of Asia-Pacific urban residents in slums with proper urban planning can have adequate shelter and basic services through proper urban planning.”

UNESCAP believes, this would be possible, only in case of “on-site slum upgrading” which would “mean improving the physical, social, economic and environmental conditions of an existing informal settlement – without displacing the people who live there.” It emphasizes, “Upgrading informal communities is the least expensive and most humane way of improving a city’s much-needed stock of affordable housing rather than destroying it. Unlike resettlement, upgrading causes minimal disturbance to people’s lives and to the delicate networks of mutual support in poor communities.”

Suggesting how it should happen, the paper says, “Urban poor groups take an active role in savings, surveying, planning and working with city authorities to make large-scale citywide upgrading possible. This is happening in more than ten Asian countries and represents an important shift in the role of the urban poor in improving their land and housing situation. Underpinning this, new financial systems linking community savings into larger city and national development funds allow the upgrading to materialize. The emphasis is on flexible financing, giving community groups the freedom to plan, to implement and to use the available funds to solve their housing and land problems

The argument for “on-site slum upgradation” has found favour in another study, “Housing Solutions: A Review of Models”, by Pratika Hingorani, prepared for the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS). Referring to how this was successfully carried out in Ahmedabad, the study says, slum network partnership (SNP) is “more successful model of slum upgradation” as it created a “unique partnership between local government, NGOs, private industry and slum communities to design, finance and implement slum upgrading projects”.

The aim in Ahmedabad was to “improve linkages with citywide infrastructure and services”, and the objectives included “improve the physical and non-physical infrastructure facilities within selected slum areas; to facilitate the process of community development; and to develop a city-level organization for slum networking and infrastructure.” In the first phase, SNP was undertaken as a three-way partnership (40-30-30) between Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, a local private sector textile firm Arvind Mills (acting through their Sharda trust), and the slum communities themselves. “The NGOs, SAATH and SEWA’s Mahila Housing Trust that had a history of working in the communities were also key partners and provided micro financing facilities in addition to other community mobilization efforts. The approximate upgrading cost of Rs 3,000 per dwelling unit was shared by the parties as above, with slum dwellers able to take loans from SEWA and SAATH in order to make contribution.”

In order to encourage slum dwellers to continue to invest in their homes, the AMC agreed to “extend written assurance for a 10 year secure tenure to households participating in their programme.” This proved crucial. Though the Arvind Mills pulled out, between 1996 and 2005, SNP upgraded 8,400 dwelling units – serving an estimated 39,000 people. Funded as an 80:20 AMC-slum community split, it focused on infrastructure provisions – e.g. individual taps, bathrooms, street lighting and paved roads, apart from public health. The author comments, “The project has been widely regarded as a success and as recognition of the attempts and investments of the poor to enter the formal housing market.”

Yet, it threw up issues related with not just private sector participation, but tenure. Pointing towards the need to solve the latter problem urgently in case such an experiment has to succeed, the author underlines, “The issue of tenure is not always clearcut depending on the nature of land ownership in the city or state… About 75 per cent of Ahmedabad slums are located on private lands that were actually sold to slum dwellers many years ago. However, many of those private owners now deny that the sale as a result of which there are a multiplicity of landowners and claims.”

Though the slum dwellers who participated in SNP were encouraged to invest in their house by guaranteeing that they would not be evicted by providing a secure tenure of a decade, the fear of eviction hung on their head. Thus, the author quotes how power connections were provided by the electricity company only after the households signed an “indemnity bond that they will not pursue legal proceedings” against the company if they were “evicted or relocated from their homes.”

It has been found that securing tenure and community participation alone can prove crucial for any slum upgradation programme. Experts cite the Baan Mandong (secure housing) project in Thailand, in this context, which is being implemented since 2003 across the country. “The programme has led to upgraded housing conditions for more than 90,000 households with low-interest government loans, through the Community Organizations Development Institute (CODI)”, says UNESCAP.

Under the Baan Mandong project, points out the IIHS study by Pritika Hingorani, “infrastructure subsidies and money for soft loans” were channeled through the slum communities. “Communities are responsible for managing their won budget through which they must finance infrastructure and shelter upgrades and secure land tenures themselves”, she underlines, adding, “This is a radical change in thinking from previous programmes – whether public housing programmes, slum upgrading or sites and services projects – where responsibility for making land available rested squarely with the government.” It helped counter the “argument often put forth – that there is no urban land in central locations in particular, on which to house the poor.”

The tenure issue was solved like this: For a slum community to be eligible to participate, they must first set up a savings and credit group in which all the residents must be members. The savings group would pool together community savings to supplement the external funds that would be received through the programme. Next, community cooperatives would be established to act as the collective legal entity in whose name the land should be acquired, and who will receive the subsidies, loans and other funds.

Thus, slum communities, acting through their community groups were responsible for finding the land on which secure tenure can be obtained. This land could be all or a portion of the land they occupied, or an alternative site, and could be public or private land. Negotiations would then ensue to determine the type of tenure – for example, leasehold, freehold – that the slum communities would have, and the price at which this will be obtained.

CODI would then loan the money for this transaction to the community at a subsidized interest rate. Loans would subject to a cap usually determined on a per household basis. CODI also would loan money for shelter upgradation to community groups who they further lend the money to their members, at a slightly higher rate of interest. “Using this method more than 90 per cent of the communities in the programme have managed to get substantially more secure tenure than before. Once tenure is secured, infrastructure subsidies from national and local government help pay for the cost of internal and connecting infrastructure to the site”, the IIHS study underlines.

There is a strong view among those who have worked with slum dwellers that this type of approach could have been suitable in Ahmedabad and other Indian cities, and the SNP was in fact moving in that direction alone. The urgency of it remains even today, as the IIHS study underlines, “As part of the 2006-12 City Development Plan for Ahmedabad, it was noted that 32.4 per cent of the city’s population still lived in slums. A significant portion of these families was below the poverty line. Moreover, slums were treated as separate entities in the city, without any linkages to the main city or its infrastructure.”

However, “State of Asian Cities 2010/11” a report jointly prepared by UNESCAP and UNHABITAT, suggests how failure to go ahead with slum upgradation in Ahmedabad led to continuance of poor living conditions in Ahmedabad’s slums. Schemes such as Baan Mandong in Bangkok showed “that a citywide slum upgrading approach” became “effective”. This was against the “piecemeal, project based improvement of a few slums” in Ahmedabad. Ahmedabad’s slum networking programme, designed to take in all the slums in the city, remained a pilot project. No doubt, civil society took care of community mobilization and development while municipal authorities acted as facilitators by severing the link between tenure status and service provision by issuing ‘no-objection certificates’ which enable those who reside in houses of less than 25 sq. m. to connect to the water network.

Even then, things did not develop any further. The UNESCAP-UNHABITAT study says, “Poor quality of shelter, where any at all, poses a major threat to health in urban slums. Compelling evidence links various communicable and non-communicable diseases, injuries and psychosocial disorders to the risk factors inherent to unhealthy living conditions, such as faulty buildings, defective water supplies, substandard sanitation, poor fuel quality and ventilation, lack of refuse storage and collection, or improper food and storage preparation, as well as poor/unsafe locations, such as near traffic hubs, dumpsites or polluting industrial sites…”

It adds, “The result is that in Ahmedabad, for instance, infant mortality rates are twice as high in slums as the national rural average. Slum children under five suffer more and die more from diarrhoea or acute respiratory infections than those in rural areas. On average, slum children in Ahmedabad are more undernourished than the average in the whole of Gujarat state.”

Even as the Gujarat government is planning to come up with a new slum policy 2013, with “rehabilitation” of the slum-dwellers with the help of private developers as the key thrust, available literature suggests that any effort to uproot slum dwellers would mean further heightening their already vulnerable status.

Recently, in a paper, “Low Carbon Green Growth Roadmap for Asia and the Pacific”, providing a roadmap for citywide slum upgradation, United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP) said that “the poor and the vulnerable in cities and towns can aspire to have security, shelter, basic infrastructure and services with citywide slum upgrading”, adding, “Up to 35 per cent of Asia-Pacific urban residents in slums with proper urban planning can have adequate shelter and basic services through proper urban planning.”

UNESCAP believes, this would be possible, only in case of “on-site slum upgrading” which would “mean improving the physical, social, economic and environmental conditions of an existing informal settlement – without displacing the people who live there.” It emphasizes, “Upgrading informal communities is the least expensive and most humane way of improving a city’s much-needed stock of affordable housing rather than destroying it. Unlike resettlement, upgrading causes minimal disturbance to people’s lives and to the delicate networks of mutual support in poor communities.”

Suggesting how it should happen, the paper says, “Urban poor groups take an active role in savings, surveying, planning and working with city authorities to make large-scale citywide upgrading possible. This is happening in more than ten Asian countries and represents an important shift in the role of the urban poor in improving their land and housing situation. Underpinning this, new financial systems linking community savings into larger city and national development funds allow the upgrading to materialize. The emphasis is on flexible financing, giving community groups the freedom to plan, to implement and to use the available funds to solve their housing and land problems

The argument for “on-site slum upgradation” has found favour in another study, “Housing Solutions: A Review of Models”, by Pratika Hingorani, prepared for the Indian Institute for Human Settlements (IIHS). Referring to how this was successfully carried out in Ahmedabad, the study says, slum network partnership (SNP) is “more successful model of slum upgradation” as it created a “unique partnership between local government, NGOs, private industry and slum communities to design, finance and implement slum upgrading projects”.

The aim in Ahmedabad was to “improve linkages with citywide infrastructure and services”, and the objectives included “improve the physical and non-physical infrastructure facilities within selected slum areas; to facilitate the process of community development; and to develop a city-level organization for slum networking and infrastructure.” In the first phase, SNP was undertaken as a three-way partnership (40-30-30) between Ahmedabad Municipal Corporation, a local private sector textile firm Arvind Mills (acting through their Sharda trust), and the slum communities themselves. “The NGOs, SAATH and SEWA’s Mahila Housing Trust that had a history of working in the communities were also key partners and provided micro financing facilities in addition to other community mobilization efforts. The approximate upgrading cost of Rs 3,000 per dwelling unit was shared by the parties as above, with slum dwellers able to take loans from SEWA and SAATH in order to make contribution.”

In order to encourage slum dwellers to continue to invest in their homes, the AMC agreed to “extend written assurance for a 10 year secure tenure to households participating in their programme.” This proved crucial. Though the Arvind Mills pulled out, between 1996 and 2005, SNP upgraded 8,400 dwelling units – serving an estimated 39,000 people. Funded as an 80:20 AMC-slum community split, it focused on infrastructure provisions – e.g. individual taps, bathrooms, street lighting and paved roads, apart from public health. The author comments, “The project has been widely regarded as a success and as recognition of the attempts and investments of the poor to enter the formal housing market.”

Yet, it threw up issues related with not just private sector participation, but tenure. Pointing towards the need to solve the latter problem urgently in case such an experiment has to succeed, the author underlines, “The issue of tenure is not always clearcut depending on the nature of land ownership in the city or state… About 75 per cent of Ahmedabad slums are located on private lands that were actually sold to slum dwellers many years ago. However, many of those private owners now deny that the sale as a result of which there are a multiplicity of landowners and claims.”

Though the slum dwellers who participated in SNP were encouraged to invest in their house by guaranteeing that they would not be evicted by providing a secure tenure of a decade, the fear of eviction hung on their head. Thus, the author quotes how power connections were provided by the electricity company only after the households signed an “indemnity bond that they will not pursue legal proceedings” against the company if they were “evicted or relocated from their homes.”

It has been found that securing tenure and community participation alone can prove crucial for any slum upgradation programme. Experts cite the Baan Mandong (secure housing) project in Thailand, in this context, which is being implemented since 2003 across the country. “The programme has led to upgraded housing conditions for more than 90,000 households with low-interest government loans, through the Community Organizations Development Institute (CODI)”, says UNESCAP.

Under the Baan Mandong project, points out the IIHS study by Pritika Hingorani, “infrastructure subsidies and money for soft loans” were channeled through the slum communities. “Communities are responsible for managing their won budget through which they must finance infrastructure and shelter upgrades and secure land tenures themselves”, she underlines, adding, “This is a radical change in thinking from previous programmes – whether public housing programmes, slum upgrading or sites and services projects – where responsibility for making land available rested squarely with the government.” It helped counter the “argument often put forth – that there is no urban land in central locations in particular, on which to house the poor.”

The tenure issue was solved like this: For a slum community to be eligible to participate, they must first set up a savings and credit group in which all the residents must be members. The savings group would pool together community savings to supplement the external funds that would be received through the programme. Next, community cooperatives would be established to act as the collective legal entity in whose name the land should be acquired, and who will receive the subsidies, loans and other funds.

Thus, slum communities, acting through their community groups were responsible for finding the land on which secure tenure can be obtained. This land could be all or a portion of the land they occupied, or an alternative site, and could be public or private land. Negotiations would then ensue to determine the type of tenure – for example, leasehold, freehold – that the slum communities would have, and the price at which this will be obtained.

CODI would then loan the money for this transaction to the community at a subsidized interest rate. Loans would subject to a cap usually determined on a per household basis. CODI also would loan money for shelter upgradation to community groups who they further lend the money to their members, at a slightly higher rate of interest. “Using this method more than 90 per cent of the communities in the programme have managed to get substantially more secure tenure than before. Once tenure is secured, infrastructure subsidies from national and local government help pay for the cost of internal and connecting infrastructure to the site”, the IIHS study underlines.

There is a strong view among those who have worked with slum dwellers that this type of approach could have been suitable in Ahmedabad and other Indian cities, and the SNP was in fact moving in that direction alone. The urgency of it remains even today, as the IIHS study underlines, “As part of the 2006-12 City Development Plan for Ahmedabad, it was noted that 32.4 per cent of the city’s population still lived in slums. A significant portion of these families was below the poverty line. Moreover, slums were treated as separate entities in the city, without any linkages to the main city or its infrastructure.”

However, “State of Asian Cities 2010/11” a report jointly prepared by UNESCAP and UNHABITAT, suggests how failure to go ahead with slum upgradation in Ahmedabad led to continuance of poor living conditions in Ahmedabad’s slums. Schemes such as Baan Mandong in Bangkok showed “that a citywide slum upgrading approach” became “effective”. This was against the “piecemeal, project based improvement of a few slums” in Ahmedabad. Ahmedabad’s slum networking programme, designed to take in all the slums in the city, remained a pilot project. No doubt, civil society took care of community mobilization and development while municipal authorities acted as facilitators by severing the link between tenure status and service provision by issuing ‘no-objection certificates’ which enable those who reside in houses of less than 25 sq. m. to connect to the water network.

Even then, things did not develop any further. The UNESCAP-UNHABITAT study says, “Poor quality of shelter, where any at all, poses a major threat to health in urban slums. Compelling evidence links various communicable and non-communicable diseases, injuries and psychosocial disorders to the risk factors inherent to unhealthy living conditions, such as faulty buildings, defective water supplies, substandard sanitation, poor fuel quality and ventilation, lack of refuse storage and collection, or improper food and storage preparation, as well as poor/unsafe locations, such as near traffic hubs, dumpsites or polluting industrial sites…”

It adds, “The result is that in Ahmedabad, for instance, infant mortality rates are twice as high in slums as the national rural average. Slum children under five suffer more and die more from diarrhoea or acute respiratory infections than those in rural areas. On average, slum children in Ahmedabad are more undernourished than the average in the whole of Gujarat state.”

---

To read how successful was the now-abandoned integrated slum development project of Ahmedabad, please click HERE

To read how successful was the now-abandoned integrated slum development project of Ahmedabad, please click HERE

Comments